Monday, May 15, 1865

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

- Proceedings

- Louis Weichmann

- John M. Lloyd

- John M. Lloyd (cont.)

- Mary Van Tyne

- Billy Williams

- Bernard Early

- James Henderson

- Samuel Streett

- Lyman Sprague

- David Stanton

- David Reed

- James Pumphrey

- Brooke Stabler

- Peter Taltavull

- Joseph Dye

- John Buckingham

- James Ferguson

- Theodore McGowan

- Henry Rathbone

- William Withers

- Brooke Stabler (cont.)

- Joe Simms

- John Miles

- John Selecman

- Recollections

- Newspaper Descriptions

- Visitors

- References

Proceedings

The court convened at 10 o’clock.[1]

Present: All nine members of the military commission, the eight conspirators, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, Assistant Judge Advocates Bingham and Burnett, the recorders of the court, lawyers Frederick Aiken, John Clampitt, Walter Cox, William Doster, Thomas Ewing, Reverdy Johnson, and Frederick Stone.

Seating chart:

There are conflicting reports as to the seating arrangements of the conspirators on this day. According to the Evening Star newspaper, the male conspirators sat in the same manner as Saturday. According to the Washington Chronicle and the New York World, however, Dr. Mudd was moved from being at the end of the prisoners’ dock, to a spot next to Samuel Arnold:

“The prisoners sat in the order we described in our issue of Sunday, with the exception of Dr. Mudd, who took up a position near to Samuel Arnold, but separated from him by a guard.”[68]

All sources agree that tomorrow (Tuesday, May 16) Dr. Mudd would be seated next to Arnold (and his guard) and would remain there for the rest of the trial. Whether Mudd actually took this seat today is unclear, but it seems likely that he did.

Mrs. Surratt certainly changed positions today and was moved away from the table with the lawyers and was, instead, placed in a seat at the end of the prisoners’ dock separated by a guard:

“Mrs. Surratt was sitting on the floor of the court-room at the end of the platform on which were the other prisoners.”[37]

Edman Spangler presented Thomas Ewing, Jr. to act as his counsel.

Ewing was now representing Samuel Arnold, Dr. Mudd and Edman Spangler. All of the conspirators now had legal representation.

Acting on behalf of his new client, Thomas Ewing asked permission to remove his client’s earlier pleas of “Not Guilty” to the charge and specification against him as it had been put in before Spangler had representation. This was allowed. Ewing then presented a plea against the jurisdiction of the court in the same manner he had done for Samuel Arnold during the last court session. JAG Holt replied, once again, that the military commission had the proper jurisdiction to try this case. The courtroom was cleared while the commission deliberated on this matter. When it reconvened, JAG Holt announced that the commission had overruled Spangler’s plea. Ewing then attempted the same move he had tried in Dr. Mudd and Arnold’s cases and presented an application for Spangler to receive a separate trial from the other conspirators. This application was overruled and Spangler re-entered his “Not Guilty” pleas to the charge and specification.

Michael O’Laughlen, via his counsel Walter S. Cox, pursued the same course of action as stated above with the same failed results.[2]

The reading of the prior session’s testimony then began.

After the reading of Louis Weichmann’s testimony was completed, Reverdy Johnson, one of Mary Surratt’s counselors, asked the court permission to cross examine the witness as he had left early during Weichmann’s testimony on Saturday. After some deliberation the commission allowed the cross examination but stated that hereafter rules would be laid down regarding the cross examination of witnesses.[3]

Testimony began

Louis J. Weichmann, a lodger at Mary Surratt’s D.C. boarding house and former classmate of John Surratt, was cross examined by Thomas Ewing and Reverdy Johnson. Ewing asked Weichmann about the circumstances regarding Booth’s introduction to John Surratt by way of Dr. Mudd. Johnson asked about Weichmann’s trip to Surrattsville with Mrs. Surratt on the Tuesday preceding the assassination. Lloyd had previously testified that this trip occurred on Monday and Johnson was happy Weichmann poked holes in Lloyd’s timeline.[4]

After Weichmann’s cross examination was complete, the reading of the prior session’s testimony resumed. During the reading of John M. Lloyd’s testimony, the government immediately recalled Lloyd likely utilizing the precedent Johnson had set when he had recalled Weichmann.[5]

Testimony resumed

John M. Lloyd, the tenant of Mrs. Surratt’s tavern, was presented with two carbine rifles by JAG Holt. He testified that he believed they were the same ones left by John Surratt at the tavern. One of the carbines was the one picked up by David Herold during the escape.[6]

These carbines were entered into evidence. Exhibit 25 was the carbine taken from Booth and Herold at the Garrett farm (pictured above) and Exhibit 26 was the carbine they left at the tavern.

After this brief “identification” of the carbines, the reading of the prior session’s testimony was resumed yet again.

Break

Reading of the testimony was finally completed at around 1:30 pm. A short break for lunch was then enacted.

“The court has taken a respite for lunch, and the prisoners and their guards file off to their cells. The whole room rings with the harsh clank of their irons, and the spectators rush to see the operation of removing the criminals. A soldier carries in each hand the heavy cannon balls attached to the limbs of Payne and Abzerott, for otherwise they could hardly move a step. Mrs. Surratt’s fetters jangle underneath her skirts – and so the sad, motley, impressive procession moves off to the dungeons, of which General Hartranft at the head, carries the huge keys.”[77]

At 2:00 pm the court reopened.

Testimony resumed

John M. Lloyd, the tenant of Mrs. Surratt’s tavern, asked to address the commission with a voluntary statement. Upon hearing the testimony of Weichmann earlier, Lloyd stated that he believed he was mistaken regarding when he met Mrs. Surratt in the week prior the assassination. He conceded that Weichmann’s testimony of Tuesday, not Monday was correct. He also admitted to no longer being certain as to where he placed the wrapped package Mrs. Surratt gave him on the day of the assassination, despite his earlier testimony claiming he took it upstairs. In this statement he reiterated that he was “somewhat in liquor” during his conversation with Mrs. Surratt on the day of the assassination.[7]

Mary Ann Van Tyne, the owner of a boarding house at 420 D Street in D.C., testified about Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen’s residence in her home from about February 10 – March 20, 1865. John Wilkes Booth was a frequent visitor to her home looking for Arnold and O’Laughlen during that time. Arnold told Mrs. Van Tyne that the three men were in the oil business together. During Booth’s performance at Ford’s Theatre on March 18, O’Laughlen presented Mrs. Van Tyne with complimentary tickets to see the show. Mrs. Van Tyne was asked to identify Arnold and O’Laughlen on the stand which she did. She was shown Exhibit 1, the picture of Booth and was asked to identify it. After putting on her glasses, she stated that, while it wasn’t the best picture of Booth, it was the same man.[8]

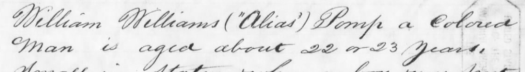

Note: The trial of the Lincoln conspirators was unique for the Civil War time period in that African American witnesses were allowed to testify openly against the eight white defendants. Only three years prior to Lincoln’s assassination, in 1862, an amendment was made to the District of Columbia Emancipation bill that prohibited the exclusion of witnesses based on race in D.C. with most federal courts following the example of the state or jurisdiction they were housed in. The black men and women who testified at the conspiracy trial consisted of those born free and those who had, until recently, been held in bondage. In fact in the case of Dr. Mudd, several of the men and women he had enslaved testified against him, which wouldn’t have been possible in other courts in other jurisdictions. In period documents, trial transcripts, and newspaper accounts the statements of African American witnesses were often labeled with the word “colored”. This term is unacceptable today but it does help us to know the identities of the brave men and women who fought against the racial prejudices of their time to exercise their long denied legal rights. The following witness, William/Billy “Pomp” Williams, was the first black witness to take the stand.

Billy “Pomp” Williams, an African American florist from Baltimore, testified about having delivered two letters on John Wilkes Booth’s behalf in March of 1865. Williams was unable to recall the exact date, but at some point in mid to late March he came across John Wilkes Booth as the actor was at the door of Barnum’s Hotel in Baltimore. Booth asked Williams to deliver two letters: one to an address on Fayette Street and another to a mutual acquaintance of theirs, Michael O’Laughlen, whose family lived on Exeter Street. As a child, Williams had lived with the Booth family in Baltimore and was familiar with their neighbors, the O’Laughlens. Williams delivered the letter on Fayette Street first, not knowing who it was addressed to for he could not read. It was later determined to be the address of Samuel Arnold’s home. Having some work to do, Williams did not immediately deliver the note to O’Laughlen. During the course of his work delivering flowers at the Holliday Street Theater, Williams saw Michael O’Laughlen in the dress circle attending a matinee. Williams gave O’Laughlen the letter from Booth in the theater. Both Thomas Ewing and Walter Cox, defense attorneys for Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, objected to Williams’ testimony, stating that the mere receipt of letters did not prove any degree of guilt. These objections were overruled after the prosecution noted that the purpose of this testimony was to further demonstrate the intimate nature of Arnold and O’Laughlen to John Wilkes Booth in Baltimore much like Mrs. Van Tyne’s previous testimony established this fact in Washington.[9]

Bernard J. Early, was a Baltimore tailor, and a friend of Michael O’Laughlen’s. Early testified about travelling from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. with O’Laughlen and others on the day before the assassination. The purpose of the trip was to witness the celebratory Grand Illumination and to take part in the festivities. Early testified at length about his and O’Laughlen’s movements in D.C. over the course of April 13, 14, and 15th. Which, on the afternoon of April 13th and the morning of April 14th, included stops at the National Hotel, where John Wilkes Booth resided. On April 13th, the visit to the National was brief with O’Laughlen telling Early the party he wished to meet with was not present. Upon their return on the morning of the 14th, Early used the bathroom and O’Laughlen made an attempt to see John Wilkes Booth. Early and another acquaintance waited for O’Laughlen in the lobby of the hotel for about 45 minutes. They had a card sent up to Booth’s room but it was returned stating that no one was there. Early left the National and, within an hour, O’Laughlen rejoined them at a bar. Early was not sure if O’Laughlen actually met with John Wilkes Booth and apparently did not ask. While Early vouched for O’Laughlen’s whereabouts for most of the night of the 13th and the 14th, he equally admitted to being very smart in liquor on both nights. On the afternoon of the 15th, the entire group returned by train to Baltimore and Early continued to accompany O’Laughlen in that city.[10] On May 25th, Bernard Early would be recalled, this time testifying for O’Laughlen’s defense.

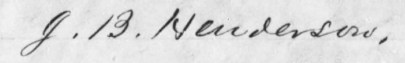

James B. Henderson, a U.S. naval ensign, was among the group of men who visited Washington, D.C. on April 13th, 14th, and 15th with Michael O’Laughlen. While Henderson took part in most of the revelry that was described by the prior witness, Bernard Early, Henderson was only asked if Michael O’Laughlen visited John Wilkes Booth during their time in Washington. Henderson only stated that O’Laughlen told him on Friday that he was to see Booth in the morning. Henderson did not state whether this meeting took place.[11] On June 12th, Henderson would be recalled by O’Laughlen’s defense.

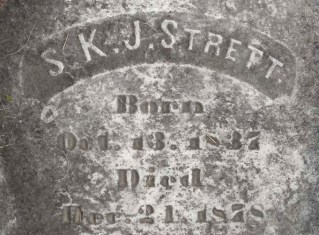

Samuel K. J. Streett, a Union sergeant stationed at D.C.’s Camp Stoneman, spoke about having known John Wilkes Booth and Michael O’Laughlen from the Baltimore neighborhood where they all grew up. Streett testified about having seen Booth talking with Michael O’Laughlen outside of a house in D.C. in either late March or early April. Streett did not hear what they spoke about nor could he identify a third individual who was there. The prosecution used this to further connect O’Laughlen with Booth.[12]

Lyman S. Sprague, one of the proprietors of the Kirkwood House Hotel, testified about being present with Detective John Lee when the latter searched George Atzerodt’s rented room.[13] Sprague saw Lee discover a revolver under Atzerodt’s pillow but did not see the rest of the search as he was called back down to the hotel office.

David Erasmus Stanton, a nephew of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, testified about seeing a man he believed to have been Michael O’Laughlen at the Secretary of War’s house on the evening of April 13, 1865. This was during the night of the grand illumination and the man wandered into the house and asked where the Secretary of War was. After determining the man was unknown to the family, David asked the man to exit the house which he did. Though General Grant was at the Secretary’s house, the man did not inquire about him. The man joined the crowd of revelers in front of the Secretary’s house.[14] While two other witnesses would testify about Michael O’Laughlen being at Stanton’s home, his defense would produce several witnesses of their own attesting to the fact that O’Laughlen was drinking with his friends during the time period where he was supposedly seen at the Secretary of War’s home.

David C. Reed, a Washington, D.C. tailor, swore he saw John Surratt (pictured below) in Washington on the morning of Lincoln’s assassination. Reed claimed to have a very passing acquaintanceship with Surratt from when he was a boy. He testified as to have seen John Surratt pass him on the street where the two exchanged a nod.[15] While John Surratt was still a wanted man at this time, he was not on trial himself. The point of this testimony, and the testimony of others that followed claiming to see John Surratt in D.C. on April 14th, was likely to implicate Mary Surratt as having lied to authorities about the whereabouts of her son. When John Surratt was caught and put on trial himself two years later, his defense would do a good job of discrediting the testimonies of people like David Reed and prove the fact that Surratt was in Elmira, New York on the night of the assassination.

James W. Pumphrey owned a livery in Washington, D.C. He testified about how Booth reserved and then picked up a horse from his stables on the afternoon of Lincoln’s assassination. Booth had been in the business of renting horses from Pumphrey for a month or six weeks prior to the assassination. The first time Booth went to Pumphrey’s he brought along John Surratt who vouched for him. On the day of the assassination, Pumphrey joined Booth for a drink after the actor had picked up his horse. Pumphrey also warned Booth that his horse did not like to be tied up and that it was best to have someone hold her. During his testimony, Pumphrey was given Exhibit 1, Booth’s photograph, to identify.[16]

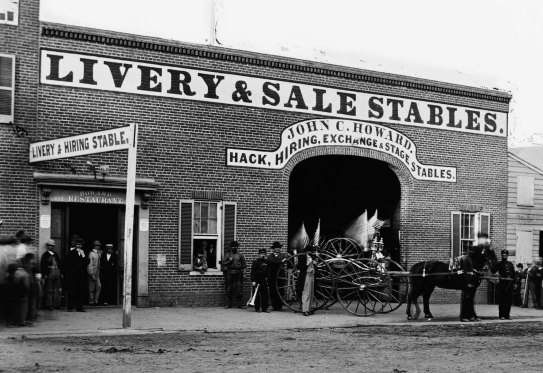

Brooke Stabler, the manager of Howard’s Livery Stable, spoke about his familiarity with John Wilkes Booth, George Atzerodt, and John Surratt. Stabler testified that John Surratt kept two horses at his stable, one of which was blind in one eye. John Wilkes Booth paid for the upkeep of the animals and John Surratt wrote a note in February allowing George Atzerodt free access to take out his horses whenever he desired. Stabler stated the three men were often together at his stables using the animals and renting others. On March 31st the two horses were taken away from Howard’s by George Atzerodt. Stabler was asked if he could recognize the one eyed horse if he saw it. He answered in the affirmative and was then asked by the court to go and visit the government stables at 7th and I streets to look at a horse in their possession and report back. Stabler then left.[17]

During his testimony, Stabler identified the note from John Surratt which granted George Atzerodt use of his horses. This note was entered into evidence as Exhibit 27.

Peter Taltavull, a member of the U.S. Marine Band, was the co-owner of the tavern connected to Ford’s Theatre called the Star Saloon. He testified that John Wilkes Booth entered his establishment on the night of April 14th and had a drink before he shot the President. Additionally, Taltavull stated that on either April 13th or 14th (he could not recall which), David Herold approached him at the bar at between six or seven o’clock and inquired if John Wilkes Booth had been in. Taltavull replied he had not seen him and Herold left.[18]

Sgt. Joseph M. Dye, a Union soldier stationed at Camp Berry near Washington, testified about seeing three men outside of Ford’s Theatre in the hour leading up to Lincoln’s assassination. Dye and another soldier were waiting outside of Ford’s in hopes of catching a glimpse of the President and General Grant as they left the theater. Dye was unaware that, despite advertisements to contrary, Grant did not join the Lincolns at the theater that night. In the group of three men Dye observed, one repeatedly poked his head into the lobby of Ford’s Theatre to check the time. He would then call out the time to the other two who were waiting outside. When the time of 10:10 was announced, one of the men entered the theater while the other two conversed for a moment before one of them walked down the street. Sgt. Dye was shown Exhibit 1, a photograph of John Wilkes Booth, and identified it as one of the men he saw though he stated the man’s mustache and hair were longer than what was shown in the picture. Dye also stated that he believed another of the men was Edman Spangler, except that the man he saw had a mustache.[19] Sgt. Dye’s testimony is not reliable and changes drastically upon different retellings. He would later be called as a prosecution witness at the trial of John Surratt, where he would identify Surratt as the man announcing the times. However, in his first statement to authorities he makes it clear that the most fancy dressed of all the men was the one who was announcing the times and that that man is also the one who enters Ford’s Theatre. In addition, after giving his initial statement, Dye was taken to the Old Capitol Prison to look at Edman Spangler and another Ford’s Theatre employee named James Gifford to see if either one of these men were among the group of three he saw. At that time, he stated that neither man looked familiar, contradicting his later identification of Spangler.[20]

John E. Buckingham, the doorkeeper at Ford’s Theatre, testified about seeing and briefly conversing with John Wilkes Booth as the actor checked the time and peeked into the theater auditorium before assassination Lincoln. Buckingham did not see the assassination itself, but witnessed Booth after he had jumped to the stage and as he ran off. The defense attorneys questioned Buckingham about Spangler’s whereabouts that night. Buck replied he never saw Spangler at the front of the house. Buckingham also asserted that, to his memory, Edman Spangler had never worn a mustache.[21] These questions were to counter the prior testimony of Sgt. Dye.

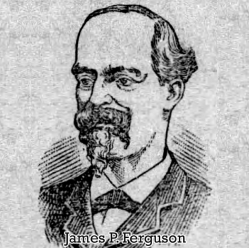

James P. Ferguson, the proprietor of the Greenback Saloon on the north side of Ford’s Theatre, was very familiar with John Wilkes Booth and was present inside of Ford’s Theatre when Lincoln was assassinated. Ferguson testified about seeing Booth riding his rented horse earlier on the day of the assassination, showing off her speed. Ferguson also testified at length about his eyewitness details of the assassination itself. Ferguson watched Booth enter the President’s box and its aftermath.[22]

Captain Theodore McGowan, an assistant adjutant general for the U.S. volunteers, testified about being present at Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. McGowan had a seat on the balcony level on the same side as the President’s box. McGowan recounted how he had to move his chair forward to allow John Wilkes Booth to pass by. McGowan also saw Booth produce a calling card of some sort which was given to the messenger sitting in front of the door to the President’s box. Booth was then allowed entry into the box.[23]

Major Henry Rathbone, a guest of the Lincolns at Ford’s Theatre on April 14th, testified about his encounter with John Wilkes Booth after the actor had shot the President. Rathbone recalled grappling with Booth after the shot rang out, being wounded by John Wilkes Booth’s knife, and the chaos that ensued after Booth jumped from the box to the stage.[24]

During Major Rathbone’s testimony he was asked to identify the knife that Booth used to stab him. Rathbone believed it very well could have been the knife used but that he only saw the gleam of it. The knife was entered into evidence as Exhibit 28.

William Withers, Jr., the orchestra leader of Ford’s Theatre, testified about his run in with John Wilkes Booth backstage after the actor had assassinated the President. Withers spoke of how Booth slashed at him with his knife in order to move him out of the way so the assassin could escape. Withers was questioned by the prosecution and the court regarding the layout of the backstage when Lincoln was assassinated. With some prompting, the prosecution succeeded in getting Withers to state his opinion that the back stage passageway was unusually clear at the time of Booth’s shot.[25]

Brooke Stabler, the liveryman from Howard’s stables, was recalled he having testified earlier in the day. He had visited the government stables as ordered and had examined the one eyed horse in the government’s possession. Stabler positively identified the horses as being the same one kept at his stables by John Surratt.[26] Unknown to Stabler was that this horse actually belonged to John Wilkes Booth which is why he normally paid for its upkeep. Booth had bought the horse in Charles County, Maryland from a neighbor of Dr. Mudd’s. On the night of Lincoln’s assassination, Lewis Powell rode this horse after attacking Secretary of State William Seward.

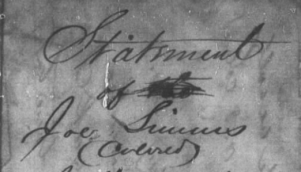

Joe Simms, an African American stagehand at Ford’s Theatre, was working up in the flies of theater on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Simms testified about seeing John Wilkes Booth earlier in the day of April 14th and then again after he shot the President and jumped from the box. Simms was asked about Booth’s familiarity with Edman Spangler and Simms recounted how Spangler helped tend to Booth’s horses and often drank with the actor.[27]

John Miles, an African American stagehand at Ford’s Theatre, was, like Joe Simms, working up in the flies on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Miles’ place in the flies put him close to a window from which he saw John Wilkes Booth ride up to the back of the theater and call for Edman Spangler. Miles testified that Booth called for Spangler three times before the stagehand appeared because he was in the process of moving scenery. Miles also testified about seeing another fellow Ford’s Theatre employee, Peanut John, holding Booth’s horse after Spangler had returned to his work. Unlike Simms, Miles did not actually witness any part of Lincoln’s assassination or Booth’s escape, but did hear the noise of horse’s hooves going out of the alley. Miles also testified of Spangler and Booth’s familiarity with one another and that, upon coming down from the flies, he ran into Spangler backstage near the door from which Booth had fled. When Miles made reference about the holding of Booth’s horse, Spangler allegedly told him, “Hush! Don’t say anything about it.”[28]

John T. Selecman, the property assistant at Ford’s Theatre, testified that on the evening of Lincoln’s assassination he witnessed John Wilkes Booth say to Edman Spangler, “Ned, you will help me all you can, won’t you?” to which Spangler replied, “Oh, yes!” This statement allegedly occurred after Booth had ridden up to the back of Ford’ Theatre. Selecman stated he did not see Booth ride up nor did he hear Booth call for Spangler from the back door, merely overhead this brief conversation. He also did not see Spangler off load the duty of holding Booth’s horse to Peanut John. Selecman was asked questions about Spangler’s duties and movements and attested to having seen Spangler, after the assassination had occurred, holding a white handkerchief and wiping his eyes.[29]

After Selecman’s testimony was concluded, JAG Holt made the recommendation to the court that the commissioners visit Ford’s Theatre in order to make a personal inspection of the premises. Holt felt that it would benefit the court to have first-hand knowledge of the backstage area given the testimony that had been given.

This suggestion was agreed to by the Commission and it was decided that the commissioners would meet informally at Ford’s Theatre at 9:30 am the next morning.[30] With that, the court adjourned at around 6:30 pm.[31]

Recollections

From General Kautz’ diary:

“The Court met at ten this morning and worked very faithfully until half past six. The testimony is very interesting…The weather continues good. Cambus Baird, a paymaster from Ripley Ohio, applied to me through the Post Office to get him a pass to visit the Court room…I am getting a great many letters asking for my autograph.”[32]

Newspaper Descriptions

“The practice of beginning each session by reading verbatim the proceedings of the day before consumes an immense amount of time; and today occupied over three hours.”[34]

“During the protracted reading of the evidence it was curious to notice the listless look that came over the prisoners, with the exception of Dr. Mudd and Mrs. Surratt. Even the wild, bold, restless eye of Payne settled down at times, but only to flash out new defiance after the briefest interval.”[35]

“While in Court the prisoners were all fastened to one chain, with the exception of Mrs. Surratt; and when going out they were unfastened – each one having its arms and legs manacled. Mrs. Surratt’s limbs are chained, which made her walk out of Court with short steps.”[36]

“The prisoners frequently consulted with their counsel during to-day, but were not allowed to speak to their fellow-prisoners.”[64]

Mrs. Surratt

“Presently Mrs. Surratt entered, draped in deep mourning and closely veiled. She appeared much depressed and tottered visibly as she made her way to her seat outside the prisoners’ dock. She leaned her head on her right hand and during the preliminary proceedings did not once raise it.”[38]

“Mrs. Surratt, veiled and draped in black, sat near the corner of the room, at the end of the railed platform on which were ranged the manacled prisoners. Leaning her bonnet against her chin and cheek in her hand, she word an appearance of fatigue, anxiety and dejection, mixed in about equal proportions. She did not verify the descriptions given of her by some of the newspapers, which have compared her to Falstaff’s widow, ‘fair, fat and forty.’ She has a large hand, large limbs, features rather large, complexion clear and healthy, dark hair and dark grey eyes. She looks like an enterprising, strong-willed woman, shrewd withal. Her shrewdness is well shown by the absence of her son John in Canada.”[39]

“We have reached the end of the line – but there is still one more of the conspirators arraigned in the charges. The sex which was no bar to her earnest participation in the darkest crime which stains the page of history, entitles her to a place more comfortable than that accorded to her fellow-criminals. In an arm-chair just outside the dock, with no sentry to inconvenience her, sits Mrs. Mary Surratt, the bereaved widow, the mother of a youthful family, the Catholic devotee, the prosaic boarding housekeeper, whom the evidence already brands as one of the most devoted and one of the most guilty of the wretched band of murderers. She is dressed in deep black, even to wearing black mittens. She is in street costume, and a thick veil covers her face, which she still more strives to hide by holding persistently before it her hand and handkerchief. In spite of these obstacles, we can still see that she is a well preserved woman of fifty, with regular and rather elegant features, and a flush still lingering on her cheek. She is not, as has been represented, an unusually large woman, but is rather graceful in figure and movement. Her hands are at liberty, but her feet, like those of the other prisoners, are fastened together by a short chain about the ankles.”[76]

“Mrs. Surratt is of large frame, but appears like a woman of considerable intelligence. She has been quite depressed for two or three days, sheds tears quietly now and then.”[40]

“Mrs. Surratt had on an entire suit of black, and kept her face closely veiled, most of the time her head resting on her hand, and her handkerchief to her face. She seems very much broken down. It is understood that her attorneys have told her she could not hope for an acquittal…In coming to and from the room she leans heavily upon the arm of an officer, and trembles from head to foot. She has no irons placed upon her; she wears no jewelry, except three plain gold rings upon her left hand.”[41]

“Mrs. Surratt sat with her face veiled, and nearer the other prisoners than on Saturday, but did not consult her counsel, as the evidence did not bear upon her case during the proceedings of to-day.”[66]

Lewis Powell

“Atzerodt and Payne seemed the most unconcerned of the prisoners…Payne directed a cool impudent stare by turns upon every person in the room. His bold eye, prominent under jaw and athletic figure gave all the marks of a bold desperate villain, but not one capable of planning a deed of cunning. When he in turn advanced to the bar to converse with his counsel he rested his manacled wrists on the rail, and stooping over it in b’hoyish style, his coal-black hair fell over his eyes in masses, adding to the savage desperation of his look. He scowled as he talked, and once or twice a grim smile appeared about his mouth, but seemed to find no lodgment about the fierce eye. He seems to affect as rowdyish a dress as possible, and to-day appeared in nothing but a close-fitting collarless blue woolen undershirt, pants of the same color and material, stocking and shoes. On Saturday he wore a steel-mixed outershirt, or gray, with collar, but – as on to-day – with no coat or vest. As he sat with his head defiantly thrown back against the wall, his tall form towered above those of his fellow prisoners on the bench.”[42]

“Payne is a villainous looking man, tall and of huge proportions, neck bare, and like a bullock, face smoothly shaven, a shock of black hair over a low forehead, and fierce eyes with small cornea, around which the white is always disagreeably visible. He leans his head straight back against the wall, and when looked at glares the looker out of countenance. He is the very man that would be selected for any atrocious deed like the murder of the Secretary of State, and a band of pirates would instinctively elect him as their captain. Any one meeting him on the street would turn around with a shudder to look at him, and a stranger meeting him face to face, would remember him for ten years. His appearance is every way very remarkable…Payne is certainly the boldest and most cunning of all these prisoners.”[43]

“A very different sort of person is the next in the row of prisoners. A tall, very athletic figure, of splendid muscular development, a massive neck, fully exposed by the open blue shirt and a most noteworthy face, make up the personal presence of the extraordinary ruffian who made the horrible attack upon Secretary Seward and his family. It is a physiognomy which one would select for a second look in any crowd, simply on account of the great animal strength of the head and utter brutality of the expression of the face. A broad, heavy jaw, unshaded by any appearance of beard; thick, protruding lips; rather a small nose, with large nostrils; clear unflinching, yet restless eyes, either black or a very dark blue-black; lowering brows; a rather low forehead, almost entirely covered by a heavy shock of unkempt black hair, falling down nearly to his eyes, a dark and clear complexion, and a head slanting down from the back like a house roof, make up the rest of the picture. His posture is exceedingly erect, even his head being constantly leaned back against the wall. There is nothing of cowardice in the look of this assassin, but rather an expression of defiant and unconquerable ugliness. He stares fiercely in turn at every person in the court-room, and never seems to wish to close his eyes even to the extent of a wink. His hands, which have been much spoken of, are not small, but very smooth and white, as if unaccustomed to labor, and his age one would fix at about twenty-five. This man, Payne, is decidedly the lion of the prisoners’ dock. Every new-comer is startled at first by his giant figure and impudent stare, and then gives a long looks as he learns that this is the only one of the conspirators who had the pluck to carry out the bloody task assigned him.”[70]

“Payne sits erect as a statue, except when he leans over to converse with his counsel, Lieutenant-Colonel Doster, law partner of J. H. Paulston, who seems to take considerable interest in this vile wretch. His countenance exhibits the most wanton recklessness while the fiend seems to be engraven upon every feature.”[44]

“Payne sat erect, with his head against the wall, maintaining the same defiant, indifferent, stoical air as on the previous days.”[65]

“He looks much younger than description has made him, and is apparently not more than twenty-one.”[45]

David Herold

“Herold looks dirty in the face and dress, and with hair apparently uncombed since the commencement of the trial, is not at all prepossessing.”[46]

“Harrold has just escaped boyhood, and has a small face, with a feeble, timid expression. He looks like a harmless though rather a mean fellow, easily led. He has a thin, inoffensive head, depressed in the regions of combativeness, and appears to be exactly the tool which Booth made of him.”[47]

“Harold takes considerable interest in the evidence and has had several long conferences over the railing with his counsel, Stone, during the taking of testimony involving others. He frequently laughed, and would more than once smile at the reporters, whose eyes would wander over towards him.”[48]

“First on the right of the line is David C. Harold, who fled with Booth through Maryland and was trapped with him in the barn at Garrett’s. Harold is a small fellow, of diminutive features and a decidedly mean and contemptable cast of countenance. Judging from his appearance, one wonders not that he cried for quarter when the cavalrymen surrounded his hiding place, but that he had courage to join the desperate fortunes of the assassin at all. His expression gives no sign of mental or moral force, and he has every appearance of abject cowardice. He has thick black hair, straight black eyebrows, sharp black eyes, and a weak irregular growth of beard on his chin and upper lip. He is seemingly about twenty-one years old. His complexion is very dingy and sallow, and he has a generally uncleanly appearance.”[69]

George Atzerodt

“Atzerodt and Payne seemed the most unconcerned of the prisoners. Atzerodt advanced to the bar in front of the raised seats, and leaning his elbow on the rail, conversed at length with his counsel, Mr. Wm. E. Doster…Atzerodt is the shortest of the lot, and has the meanest face, but us thick set, and of a build about the shoulders indicating great physical strength. He is dressed in a course suit of mixed gray.”[49]

“Atzerodt is a vulgar looking creature, but not apparently ferocious, combativeness is large but in the region of firmness his head is lacking where Payne’s is immense. He has a protruding jaw, and mustache turned up at the end, and a short insignificant looking face. He is just the man to promise to commit a murder and then fail on coming to the point. Mrs. Surratt calls him a ‘stick,’ and she is probably right.”[50]

“Abzerott is an admirable type of the lower class of Germans – short in stature, yellow in complexion and hair, meagerly supplied with beard, having light blue eyes, high cheek-bones, and neck so short and eyebrows so light that both are hardly perceptible. He has in his present plight rather a hang-dog look, is shabbily dressed, and has the general appearance of having spent much of the thirty years of his life in indoor mechanical pursuits.”[71]

“Atzeroth is the most restless and nervous of any one. His whole bearing indicates the craven coward, and the great wonder is that he was ever entrusted to do a deed of blood that could not be done in the dark. His eyes follow the Court or witnesses with rapidity, and he listens carefully to every word.”[51]

Dr. Mudd

“Dr. Mudd looks decidedly out of place, and in uncongenial company. A mild and inoffensive man in appearance, with a high bald forehead, thin yellow hair, small blue eyes, red moustache and full beard, and a sort of faded-out florid complexion, with a general air of retirement and timidity, his countenance would go far toward acquitting him of a very deep participation in the conspiracy.”[74]

“The full forehead and rather reflective cast of face of Dr. Mudd seemed much out of place among the low type of countenances of his fellows.”[52]

Samuel Arnold

“Sam Arnold, who thought he had retired from the scheme in time to save his neck, has the advantage of a seat next the window. He is an exceedingly ordinary looking young man, with a frank, open, and not unprepossessing countenance.”[75]

“There is less to convict Sam Arnold than any other; but his connections with Booth are the closest of any. He and Atzeroth seem to have been his trusted friends all the way through; but on the fatal night, and for several days previous, he does not appear on the scene. There is no doubt he knew all about the murder, and did aid and abet. He does not appear very much concerned, and looks better than any of the rest.”[53]

Michael O’Laughlen

“Michael O’Laughlin, who is accused of having ‘lain in wait’ for General Grant, but against whom so far the testimony is very slight, only proving that he has been intimate with Booth, is next in the line. He has a pallid complexion, not unlike that of Booth himself, and is on the whole far from an ill-looking man. He has very black waving hair, uneasy eyes, a heavy moustache and scanty imperial, and is about thirty years old. He has a general air of being greatly worn down by confinement and the anxiety inseparable from his position.”[72]

“O’Laughlin is charged with intending the assassination of Gen. Grant. He looks like Booth, with black hair, mustache and imperial. He would not naturally be selected for any brutal business, though bad habits have made their marks in his face.”[54]

“O’Loughlin sits next, and looks very much like Booth, as does Colonel Doster, Payne’s counsel. He has been the object of interest all afternoon, but does not indicate much feeling, one way or the other.”[55]

“McLaughlin and Spangler appear much depressed, and the former especially, looks pale and haggard.”[56]

Edman Spangler

“Spangler, the carpenter of the theater, is another whom the testimony had not borne very heavily on thus far. Nevertheless, he is the most despondent in appearance of the seven, and has an expression of being frightened nearly out of his wits at the prospect before him. He is a middle-aged man, of light complexion, features coarsened by long hard drinking, and about a week’s growth of brown beard.”[73]

“Spangler has a long face and thin head, indicating a mild disposition easily controlled by others. He looks like an average carpenter of forty, as he is, and he must have been, like Harrold, John Surratt and Arnold, the mere tool of stronger and more vicious persons.”[57]

“Spangler was doomed to day by the final testimony of the colored man who heard Booth tell him as they walked off together, fifteen minutes before the murder, ‘Now, Ned, you must stand by me to-night in this thing,’ and Ned did his part, and now he is the picture of doubt and despair alternatively playing across his face.”[58]

“The other prisoners, with the exception of McLaughlin and Spangler, wore a look of stolid indifference, while these two men seemed dejected and dispirited.”[59]

“Spangler wore a stupid air, and did not seem to feel much interest in the testimony.”[67]

Visitors

“At the green table used for the reporters were seated L[awrence. A. Gobright and F[rancis] H. Smith, of the Associated Press; C[rosby] S[tuart] Noyes and James Croggon, of the Star; Messrs. [William B.] Shaw and [Uriah Hunt] Painter, of the Philadelphia Inquirer; John B. Woods, of the Boston Daily Advertiser; A[ugustus] R. Cazauran, of the Washington Chronicle; W[illiam] A[ugustus] Croffut, of the New York Tribune; W[illiam] W. Warden, of the New York Times, and R[ichard] F. Boiseau, of the Republican.”[60]

“The small size of the room where the case is tried forbids the general admission of the public; but several distinguished visitors, including Senator [Henry] Wilson of Massachusetts and General [Gilman] Marston of New Hampshire, were allowed to indulge their curiosity this afternoon.”[61]

“To-day there were some ten or twelve reporters in Court, beside Gen. [Robert C.] Schenck, Senator Wilson, Gen. [James Mitchell] Ashley, [New York State] Senator [Charles J] Folger and other distinguished men.”[62]

“In the court-room this afternoon were a few spectators, among whom we noticed Senator Wilson, Ex-Senator [Morton Smith] Wilkinson, Gen. Schence, Gen. Marston, and Hon. Mr. Ashley, members of Congress.”[63]

Previous Session Trial Home Next Session

[1] John F. Hartranft, The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft, ed. Edward Steers, Jr. and Harold Holzer (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 97.

[2] William C. Edwards, ed., The Lincoln Assassination – The Court Transcripts (Self-published: Google Books, 2012), 121.

[3] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 15, 1865, 2.

[4] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 122 – 123.

[5] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[6] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 123 – 124.

[7] Ibid., 124.

[8] Ibid., 125 – 128.

[9] Ibid., 128 – 132.

[10] Ibid., 132 – 141.

[11] Ibid., 141.

[12] Ibid., 141 – 143.

[13] Ibid., 143 – 144.

[14] Ibid., 144 – 146.

[15] Ibid., 146 – 149.

[16] Ibid., 149 – 151.

[17] Ibid., 151 – 153.

[18] Ibid., 153 – 154.

[19] Ibid., 154 – 159.

[20] William C. Edwards and Edward Steers, Jr., ed, The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 455 – 456.

[21] Edwards, Court Transcripts, 159 – 160.

[22] Ibid., 160 – 164.

[23] Ibid., 164 – 165.

[24] Ibid., 165 – 167.

[25] Ibid., 167 – 170.

[26] Ibid., 170 – 171.

[27] Ibid., 172 – 174.

[28] Ibid., 174 – 180.

[29] Ibid., 180 – 184.

[30] Ibid., 184.

[31] Hartranft, Letterbook, 97.

[32] August V. Kautz, May 15, 1865 diary entry (Unpublished diary: Library of Congress, August V. Kautz Papers).

[33] Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 15, 1865, 2.

[34] Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), May 16, 1865, 1.

[35] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[36] Daily Constitutional Union (Washington, D.C.), May 15, 1865, 2.

[37] Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), May 15, 1865, 2.

[38] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[39] Republican, May 15, 1865, 2.

[40] New-York Tribune (New York, NY), May 16, 1865, 1.

[41] The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), May 16, 1865, 4.

[42] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[43] Tribune, May 16, 1865, 1.

[44] Inquirer, May 16, 1865, 4.

[45] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[46] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[47] Tribune, May 16, 1865, 1.

[48] Inquirer, May 16, 1865, 4.

[49] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[50] Tribune, May 16, 1865, 1.

[51] Inquirer, May 16, 1865, 4.

[52] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[53] Inquirer, May 16, 1865, 4.

[54] Tribune, May 16, 1865, 1.

[55] Inquirer, May 16, 1865, 4.

[56] Star, May 15, 1865, 2.

[57] Tribune, May 16, 1865, 1.

[58] Inquirer, May 16, 1865, 4.

[59] Union, May 15, 1865, 2.

[60] Republican, May 15, 1865, 2.

[61] Advertiser, May 16, 1865, 1.

[62] Tribune, May 16, 1865, 1.

[63] Republican, May 15, 1865, 2.

[64] The World (New York, NY), May 16, 1865, 1.

[65] The World (New York, NY), May 16, 1865, 1.

[66] The World (New York, NY), May 16, 1865, 1.

[67] The World (New York, NY), May 16, 1865, 1.

[68] Washington Weekly Chronicle (Washington, D.C.), May 20, 1865, 3.

[69] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[70] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[71] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[72] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[73] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[74] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[75] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[76] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

[77] The World (New York, NY), May 19, 1865, 1.

The drawing of the conspirators as they were seated on the prisoners’ dock on this day was created by artist and historian Jackie Roche.

Pingback: The Trial Today: May 15 | BoothieBarn

I have long wondered why Reverdy Johnson bolted from the defense of Mary Surratt. After reading General Kautz comments of May 13, I believe that Johnson was much insulted by the insinuation of disloyalty. Certainly he would be upset and his dignity insulted but as stated his remarks were “quiet and dignified.” As an attorney of many years practice and as a long-standing politician, such attacks were likely not foreign to him. I dislike historical speculation but I do not believe the indignities upon his character would be the reason he no longer participated in the trial. I would suspect he consulted regularly with his associates but apparently he left no explanation of his reasoning to abandon Mrs. Surratt. I wish he had.

Pingback: Formerly Enslaved Voices in the Lincoln Assassination Trial | LincolnConspirators.com

Pingback: Edman Spangler: “I am entirely innocent” | LincolnConspirators.com

Pingback: Samuel Arnold – Kurt's Historic Sites