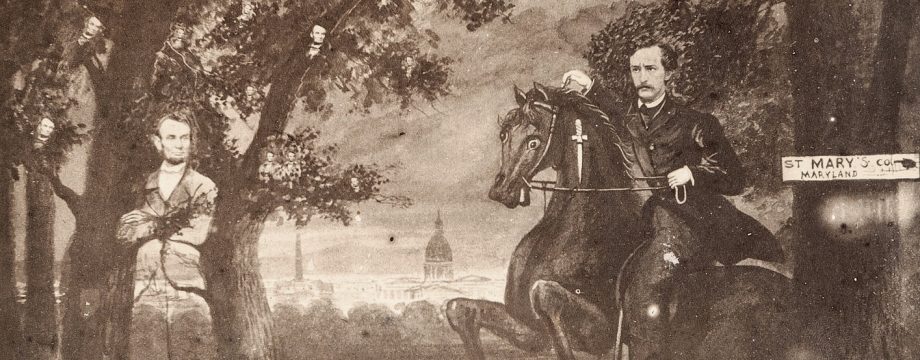

On March 20, 1869, Dr. Samuel A. Mudd walked in the front door of his Charles County, Maryland home. Such a return to one’s property would hardly be worth mentioning if not for the fact that it had been almost four years since the doctor had set foot on his farm. The last time Dr. Mudd was able to take in the land around him and the house which he called his home was on April 21, 1865, the day he was arrested for suspicion of complicity in Abraham Lincoln’s death. Since that time, Dr. Mudd had been imprisoned in nearby Bryantown, the Old Capitol Prison in D.C., and finally the Old Arsenal Penitentiary where he was put on trial by military commission. Found guilty, Dr. Mudd barely escaped with his life when he was sentenced to life imprisonment and sent to Fort Jefferson off of the coast of Florida. From July 24, 1865 through March 11, 1869, the desolate Dry Tortugas was the only home the prisoner, Dr. Mudd, had known. During his time on the island, he had tried (and failed) to escape, causing himself and the other Lincoln conspirators to suffer the consequences. In 1867, when a Yellow Fever epidemic swept the Fort causing his companion Michael O’Laughlen to die, Dr. Mudd volunteered his medical services and tended to the ill. With the common belief of the day being that those infected with Yellow Fever were contagious, Mudd’s assistance to the sick was seen as a selfless and noble act. His actions worked in his favor to help him secure a pardon in the final days of Andrew Johnson’s presidency. Nine days after leaving Fort Jefferson, Dr. Samuel Mudd stepped through the threshold of his home to greet his waiting children.

Less than a week after his homecoming, Dr. Mudd heard an unexpected knock on his door. Though you might expect him to be incredibly wary of unannounced visitors, he opened the door and welcomed a small party of men inside. Among the group was a newspaper reporter from the New York Herald. The reporter and his party had come from Washington and had spent about eight hours making their way down to the isolated Mudd farm. They wanted to speak with Dr. Mudd about his experiences regarding John Wilkes Booth and the Dry Tortugas.

“…His face grew extremely serious and he answered that of all things he wished to avoid it was newspaper publicity, simply because nothing was ever printed in connection with his name that did not misrepresent him.”

Yet, despite his apprehension and claim he did not wish to speak about the events that cost the last four years of his life, in the end, Dr. Mudd and his wife did open up about their most famous visitors and their aftermath. The following is a transcription of part of the New York Herald article that was published on March 31, 1869, just a few days after speaking with Dr. Mudd. The entire article is quite long, with the first half dealing with the author’s slow trek to get to the Mudd farm from Washington. While filled with vivid and sometimes flowery details of the journey, for ease of reading only the parts relating to the interview with Dr. Mudd are featured below. If you are interested in reading the whole article, you can do so by clicking here or the headline below.

The interview (like all the statements and correspondences from Dr. Mudd) contains a variety of truths, half-truths, omissions, and outright falsehoods regarding Booth’s relationship with Mudd and his time at the Mudd farm. Still, this interview provides an interesting and personal view of one of the more debated conspirators in the Lincoln assassination story.

…We knocked for admission at the same door that Booth did after his six hours’ ride –it took us eight – and were promptly answered by a pale and serious looking gentleman, who, in answer to our inquiry if he were Dr. Mudd, replied, “That’s my name.” It was gratifying after so long a journey to find the man you sought directly on hand and apparently prepared to furnish you will the amplest stores of information regarding his connection with Booth, &c. Having stated the object of our visit – that the Herald led an interest in learning some particulars of his experience in the Dry Tortugas and his recollections of the assassination conspirators – his face grew extremely serious and he answered that of all things he wished to avoid it was newspaper publicity, simply because nothing was ever printed in connection with his name that did not misrepresent him.

“A burned child dreads the fire,” he exclaimed, “and I have reason to be suspicious of every one. It was in this way Booth came to my house, representing himself as being on a journey from Richmond to Washington, and that his horse fell on him. Six months or so from now, when my mind is more settled and when I understand that changes have taken place in public opinion regarding me, I shall be prepared to speak freely and fully on these matters you are anxious to know about. At present, for the reason stated, I would rather not say anything.”

Having, however, convinced the doctor that it was with no motive to misrepresent his statements that we paid him this visit and tat between Booth’s case and ours there was no analogy, he invited us to pass the evening at his house and postpone our return to Washington till the morning. Left alone for a while in the parlor, an ample, square apartment, with folding doors separating it from the dining room, we began to feel an irresistible inclination to imagine two strangers on horseback riding up to the door in the dim gray of an April morning, the younger of the two lifting the other from his saddle and bother like evil stars crossing the threshold of an innocent and happy household to blast its peace forever, Dr. Mudd’s return disturbed our reveries.

The Doctor says he is thirty-five years of age, married in 1860 [sic], built the house in which he now lives after his marriage, owned a well stocked farm of about thirty acres, and was in the enjoyment of a pretty extensive practice up to the time of his arrest in 1865. The word went well and smoothly with him previous to that unhappy event. His house was furnished with all the comfort of a country gentleman’s residence. He had his horses and hounds, and in the sporting season was foremost at every fox hunt and at every many outdoor sport. He had robust health and a vigorous, athletic frame in those days, but it is very different with him now. Above the middle height, with a reddish mustache and chin whisker, a high forehead and attenuated nose, his appearance indicates a man of calm and slow reflection, gentle in manner, and of a very domestic turn. He says he was born within a few miles of this house, and has lived all his life in the country. His whole desire now it to be allowed to spend the balance of his days quietly in the bosom of his family. In his sunken, lustreless eye, pallid lips and cold, ashy complexion one can read the words “Dry Tortugas” with a terrible significance. In the prime of his years, looking prematurely old and careworn, there are few indeed who could gaze on the wreck and ravage in the face of this man before them without feeling a sentiment of sympathy and commiseration. “I have come home,” said the Doctor sorrowfully, “to find nothing left me but my house and family. No money, no provisions, no crops in the ground and no clear way before me where to derive the means of support in my present [unintelligible] condition.” There was no deception here. In the scantly furniture of the house and in the pale, sad countenance of the speaker there was evidence enough of poor and altered fortune. It was not evening and growing rapidly dark. A big fire blazed on the ample hearth, and Mrs. Mudd, an intelligent and handsome lady, with one of her children, joined the Doctor and ourselves in the conversation over the events of that memorable April morning after the assassination.

“Did you see Booth, Mrs. Mudd?” we inquired with a feeling of intense interest to hear her reply.

“Yes,” she replied, “I saw himself and Harold after they entered this parlor. Booth stretched himself out on that sofa there and Harold stooped down to whisper something to him.”

“How did Booth look?”

“Very bad. He seemed as though he had been drinking very hard; his eyes were red and swollen and his hair in disorder.”

“Did he appear to suffer much?”

“Not after he laid down on the sofa. In fact, it seemed as if hardly anything was wrong with him then.”

“What kind of a fracture did Booth sustain?” we inquired, addressing the Doctor.

“Well,” said he, “after he was laid down on that sofa and having told me his leg was fractured by his horse falling on him during his journey up from Richmond, I took a knife and split the leg of his boot down to the instep, slipped it off and the sock with it; I then felt carefully with both hands down along his leg, but at first could discover nothing like crepitation till, after a second investigation, I found on the outside, near the ankle, something that felt like indurated flesh, and then for the first time I concluded it was a direct and clean fracture of the bone. I then improvised out of pasteboard a sort of boot that adhered close enough to the leg to keep it rigidly straight below the knee, without at all interfering with the flexure of the leg. A low cut show was substituted for the leather boot, and between five and six o’clock in the morning Booth and his companions started off for a point on the river below.”

“How did Booth’s horse look after his long ride?” we inquired.

“The boy, after putting him up in the stable,” the Doctor replied, “reported that his back underneath the forward part of the saddle was raw and bloody. This circumstance tallied with Booth’s account that he had been riding all day previous from Richmond, and no suspicion arose in my mind for one instant that the man whose leg I was attending to was anything more than what he represented himself.”

“You knew Booth before, Doctor?”

“Yes,” replied the Doctor. “I was first introduced to Booth in November, 1864, at the church yonder, spoke a few words to him and never saw him afterwards until a little while before Christmas, when I happened to be in Washington making a few purchases and waiting for some friends from Baltimore who promised to meet me at the Pennsylvania House and come out here to spend the holidays. I was walking past the National Hotel at the time, when a person tapped me on the shoulder and, on turning round, I discovered it was the gentleman I was introduced to at the church about six weeks previously. He asked me aside for a moment and said he desired an introduction to John H. Surratt, with whom he presumed I was acquainted. I said that I was. Surratt and I became almost necessarily acquainted from the fact of his living on the road I travelled so often on my way to Washington, and having the only tavern on the way that I cared to visit. Booth and I walked along the avenue three or four blocks, when we suddenly came across Surratt and Weichman [sic], and all four having become acquainted we adjourned to the National Hotel and had a round of drinks. The witnesses in my case swore that Booth and I moved to a corner of the room and were engaged for an hour or so in secret conversation. That was a barefaced lie. The whole four of us were in loud and open conversation all the time we were together, and when we separated we four never met again.”

“You told the soldiers, Doctor, the course the fugitives pursued after leaving your house?”

“I did. I told them the route that Booth told me he intended to take; but Booth, it seems, changed his mind after quitting here and went another way. This was natural enough; yet I was straightway accused of seeking to set the soldiers astray, and it was urged against me as proof positive of implication in the conspiracy.”

“You must have felt seriously agitated on being arrested in connection with this matter?”

“No, sir. I was just as self-possessed as I am now. They might have hanged me at the time and I should have faced death just as composedly as I smoke this pipe.”

“What did you think of the military commission?”

“Well, it would take me too long to tell you. Suffice it to say that not a man of them sat on my trial with an unbiased and unprejudiced mind. Before a word of evidence was heard my case was prejudged and I was already condemned on the strength of wild rumor and misrepresentation. The witnesses perjured themselves, and while I was sitting there in that dock, listening to their monstrous falsehoods, I felt ashamed of my species and lost faith forever in all mankind. That men could stand up in that court and take an oath before Heaven to tell the truth and the next moment set themselves to work to swear away by downright perjury the life of a fellow man was a thing that I in my innocence of the world never thought possible. After I was convicted and sent away to the Dry Tortugas a confession was got up by Secretary Stanton, purporting to have been made by me to Captain Dutton on board the steamer, and was afterwards appended to the official report of my trial. This was one of the most infamous dodges practiced against me, and was evidently intended as a justification for the illegality of my conviction. I never made such a confession and never could have made it, even if I tried.”

“How did their treat you down to the Dry Tortugas?”

“Well, I feel indisposed to say much on that head. If I made disclosures of matters with which I am acquainted certain officers in command there might find themselves curiously compromised.”

“You did good service caring the fever plague, Doctor?”

“Well, I can say this, that as long as I acted as post physician not a single life was lost. My whole time was devoted to fighting the spread of disease and investigating its specific nature. I found that the disease does not generate the poison which gives rise to the plague. The difference between contagion and infection which I have discovered is that one generates the poison from which the fever springs and the other does not. Contagion, such a smallpox, measles, &c., generates the poison which spreads the complaint of yellow fever, typhoid fever and other such infectious diseases. It requires contact with the poison and not with the disease to infect a person, and if a thousand cases of fever were removed from the place of the disease no danger whatever need be apprehended. The Fever in the Dry Tortugas was of the same type as typhoid, and the treatment on the expectant plan – that, is watching the case the treating the symptoms as they manifest themselves.”

“Were you untrammelled in your management of the sick?”

“No, sir; there’s where I felt the awkwardness of my position. I was trammelled and consequently could not act with the independence a physician under such circumstances should have.”

The Doctor talked at considerable length on many other topics connected with his imprisonment. In replying to the remark that his feelings must have been greatly exercised at coming within sight of his old home and meeting his wife once more he said, with visible tremor, that words were entirely inadequate to express the overwhelming emotions that filled his mind. It appears that a few days before he left the Dry Tortugas a company of the Third artillery, who were on board a transport about being shipped to some other point, on seeing the Doctor walking on the parapet, set up three cheers for the man who periled his life for them in the heroic fight with the dread visitation of fever. We talked along till midnight, then retired to a comfortable leather bed, and, rising with the sun in the morning, started out homeward journey to Washington.

References:

(1869, March 31) Dr. Mudd. New York Herald, p. 10.

I have an orig. copy of a newspaper containing this interview. I have often thought that it would make a great documentary, showing the reporter and a young man who is going to take it all down in shorthand riding in a buggy to Dr. Mudd’s house (the real house), being ushered inside, sitting in the parlor with Mudd, and conducting his interview. He would show the reporter the sofa, take him upstairs, chat with him outside to show him the route Booth took, and using flashbacks with re-enactments of everything he talks about — being introduced to JWB, “bumping into” JHS, the setting for the trial with actors playing all the parts. Fort Jefferson, etc; all while Mudd continues his narration.

I will never really follow through with this idea. WHy don’t you do it?! Maybe you could play Dr. Mudd, and create some business with Mrs. Mudd, played by your bride?

Richard,

I agree with you that the newspaper reporter set-up would be a very interesting plot device to use in a documentary or short film about Dr. Mudd. Now that you’ve put the idea out there, hopefully some filmmaker in the future will take the idea and use it.

I visited the home of Dr Mudd as well as the Dry Tortugas where he was imprisoned. One of the most fascinating characters off the conspiracy and thank you once again for this article..