You’d be amazed what you can turn up nowadays with a just Google search and a friendly inquiry. A few weeks ago I was working on the Maps page of BoothieBarn looking for more sites around the country that have a connection to the Lincoln assassination. While most of the time I’m looking for the graves of certain individuals involved in the story, for some reason I decided to change my method and focus on an certain city and see what I could turn up by Googling. For no reason in particular, I chose Omaha, Nebraska as a place to search for folks connected to the assassination. I happily discovered that Omaha is the final resting place of Pvt. Augutus Lockner, a Union soldier who was saved by conspirator Lewis Powell in December of 1864. If you want to read more about that fascinating story, pick up the second edition of Betty Ownsbey’s book, Alias “Paine”: Lewis Thornton Powell, the Mystery Man of the Lincoln Conspiracy.

I also stumbled across an article from the Omaha World-Herald in which the newspaper went behind the scenes of The Durham Museum to see some of the objects in the museum’s large and varied Byron Reed collection. One of the items mentioned in the article was a playbill from Edwin Booth’s namesake theater (pictured).

I also stumbled across an article from the Omaha World-Herald in which the newspaper went behind the scenes of The Durham Museum to see some of the objects in the museum’s large and varied Byron Reed collection. One of the items mentioned in the article was a playbill from Edwin Booth’s namesake theater (pictured).

After tweeting out the image of the playbill, both myself and Carolyn Mitchell from Tudor Hall, the home of the Booth family, sent a message asking The Durham Museum if they had any other artifacts connected to the Booths or the assassination. The collection’s manager graciously searched their archives and found four other playbills for Booth’s Theatre and two 1865 newspapers announcing the news of Lincoln’s death.

The collections manager also informed us that the Byron Reed collection contained a letter written by the avenger of Lincoln himself, Sergeant Boston Corbett. She kindly photographed the letter and sent the images to us. I then contacted Steve Miller, a fellow assassination researcher and the foremost expert on Boston Corbett. I was happily surprised to find that this letter was a new discovery for him and that he had not yet come across it during his years of research. Working together, Steve and I were able to produce a transcript of the letter which had been somewhat damaged with age.

Corbett wrote the letter to his former commanding officer, the then Lieutenant of the 16th New York Cavalry that tracked down John Wilkes Booth and David Herold, Edward P. Doherty. Writing on December 1, 1866, Corbett is responding to Doherty’s request for an affidavit relating to his role in the capture of Booth. Before sharing the letter, however, some historical context is needed.

On July 26, 1866, Representative Giles Hotchkiss of New York presented to the House of Representatives the findings of the Committee of Claims in reference to the reward money. Prior to this, the War Department had presented Congress with their recommendations of how to divide up the money. Mr. Hotchkiss’ committee took the War Department’s advice when it came to the division of monies for the capture of Jefferson Davis and only made a few changes to the War Department’s allotment for reward money for the arrests of George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, and Mary Surratt. However when it came to the reward money for capture of Booth and Herold, there was much debate. Rep. Hotchkiss’ committee put forth a bill recommending that Gen. Lafayette Baker, the head of the National Detective Police who sent detectives Everton Conger and Luther Baker with Doherty and the 16th New York into Virginia, receive $17,500 in reward money. Detective Conger was also to receive $17,500. Luther Baker would get $5,000, Lieutenant Doherty would receive $2,500, and Corbett and the rest of the 16th NY would each get $1,000. This allotment did not sit well will some of the other members of the House. Several felt it unfair for Gen. Baker to receive such a lion’s share of the reward money when he was not even present at Booth’s capture. Rep. Hotchkiss replied that Gen. Baker had been the mastermind of the entire manhunt and therefore desired the highest amount, with Conger receiving the same amount since he was in charge of the group that captured Booth. This point about Conger being in charge was disputed by Lieut. Doherty who had produced papers to counter the claim. However, within the House of Representatives there was great sympathy for Everton Conger since he was a veteran who had been wounded earlier in the war.

As the debate over amounts continued, Hotchkiss seemed to become angry with his fellow lawmakers. One of the other congressmen tactlessly pressed Hotchkiss to provide more money for one of his constituents who aided in the manhunt, noting how he had presented this claim to Hotchkiss personally and was disappointed to see how little had been allotted. This exasperated Hotchkiss, leading him to express that this whole matter had been trouble from the start. Hotchkiss said he had consulted the mountains of reward claims that had been submitted to the War Department in an effort to divvy up the money as best as he could, noting that there was no protocol for him to follow. He did not like the insinuation that he was playing favorites, noting that neither Gen. Baker or the other claimants were friends of his and that he was merely doing, “the duty I was called upon to perform”.

In attempting to show his impartiality, an angry Hotchkiss decided to make a point using Lieut. Doherty:

“During this session a telegram has been shown me from Lieutenant Doherty, saying that there was a great fraud being perpetrated here, and he wanted the American Congress to stop the wheels of legislation and wait until he could be here. Lieutenant Doherty has been here pretty much all winter, and has been before me time and time again in regard to this matter. I have had rolls of documents from him, and I wish to avoid saying anything about him. But now, since he has had the impudence to come here and charge a man who has been engaged in the honest discharge of his duty, without fear or favor, one who is a stranger to all these men, who does not care personally whether they get a cent, and since gentlemen have shown the want of confidence in the committee to make the remarks they have, I feel constrained to say that I believe Lieutenant Doherty was a downright coward in this expedition.

From all the evidence, I believe that while these five men where guarding that tobacco-house where these prisoners were secreted, and while Lieutenant Colonel Conger was endeavoring to get a guard around the building, Doherty stayed under a shed, and no power could drive him out of it. And now he comes in and claims that he did the whole. Such is the evidence in the case, as it has been presented. If there is anything to contradict it, let it be brought in.”

Hotchkiss then points out that despite his strong belief that Lt. Doherty was an coward who deserved no portion of the reward money, the committee still allotted him some funds “in deference in part to popular clamour”.

Hotchkiss also spoke harshly of Boston Corbett. He said the evidence he saw supported the idea that Corbett defied orders by leaving his assigned post, made his way close to the barn where he was not supposed to be, and then shot Booth who was attempting to surrender himself. He described Corbett as, “an insane man” at the shooting of Booth. “I am told that Corbett has since died in a lunatic asylum, and he was then evidently an insane man. Yet he is given the same sum as the other soldiers receive. For a two days’ ride I think that is an ample compensation.”

While Hotchkiss provided a defense of the committee’s reasoning for their proposed reward allotments, he didn’t feel it worth a prolonged fight. After an hour of debate, Hotchkiss was tired of the insinuations from his colleagues and just wanted the whole mess to be over. Another representative had put forth an amendment to his bill, changing the amounts provided for Booth and Herold’s capture and, in the end, Hotchkiss did not fight it and the amended bill was approved. “When you cannot do as you would, you must do as you must,” Hotchkiss stated.

The amended bill still gave Everton Conger the largest share of reward money at $15,000, a decrease from Hotchkiss’ $17,500. General Lafayette Baker dropped way down from $17,500 to $3,750. Luther Baker fell from $5,000 to $3,000. Ironically, it was Lt. Doherty, Boston Corbett, and the rest of the soldiers who benefited the most from this amended bill. Doherty’s reward money went from $2,500 in Hotchkiss’ bill to $5,250 in the amended version. Corbett and all the other soldiers also got pay increases from $1,000 to $1,653.84 each. In the end, it would be these amounts that would be passed in the Senate and given out.

While Doherty ended up receiving a good deal of money, when he learned of what Giles Hotchkiss had said about him on the floor of the House of Representatives, remarks that were carried in newspapers around the country, he became very offended at the attack on his honor. On August 1st, while stationed in South Carolina, Doherty sent off a letter to the New York Herald promising a rebuttal to Hotchkiss’ lies.

“I cannot remain quiet under such charges affecting my character as a soldier, and my conduct as an officer, coming from such a quarter. In the course of a short time I shall place before the people of the United States such evidence as will convince them that the charges made by the honorable member are untrue. The language used by the member from New York, did not come to my notice until after the adjournment of Congress, and when I no longer had an opportunity of vindicating myself before that body.

Chance has connected my name with a great historical event; and I simply desire that the army with whom I served, and the people for whom I fought, should know that in the performance of my duty I was not a laggard and a coward.

Edward P. Doherty

Second Lieutenant Fifth Cavalry, U. S. Army”

Doherty quickly sent off a letter to Boston Corbett, a man he knew would support him and could help tell the real story of what happened at the Garrett farm. Corbett was still a bit of a hero for slaying Booth and Doherty was hoping he could depend on Corbett to publicly refute Hotchkiss since he, too, had been a victim of the Congressman’s lies. The very much alive and not (quite) insane former sergeant responded just as Doherty had hoped. He wrote a letter back to Doherty in South Carolina on August 6, 1866. Doherty then had the text of the letter was published in the New York Citizen on August 25th:

“God bless you, my dear sir; the slander and lie that was told by Mr. Hotchkiss, in Congress, about you, makes me love you more than ever. And I do not believe that such a wicked lie and such a malicious slander will be allowed to go altogether unpunished, or to have the effect on the public mind that was intended. I do not doubt, though, that it did have the effect desired in Congress; and I do truly believe that it was told and used there for the express purpose of getting the largest share of the reward for the Detectives, and getting the military into disgrace, and consequently the small apportionment that was made to us.

I do without hesitation pronounce the assertion that you was under a shed, and that the Detective could not force you out, to be a wicked lie. For I well know that you not only commanded the party, but commanded it well; and at the time that the house and barn of Mr. Garrett was surrounded, it was done by your orders; and that you took the leading part in all that was done there, as also in the whole expedition.

I am aware, also, that you placed me next in command to yourself before leaving Washington, giving me charge as acting orderly sergeant, and had you been killed I should myself have been in command of the party, and not the Detective. I am also aware of the fact that when you got track of the assassins, you had to send men after the Detective (Conger), who was off in another direction at the time.

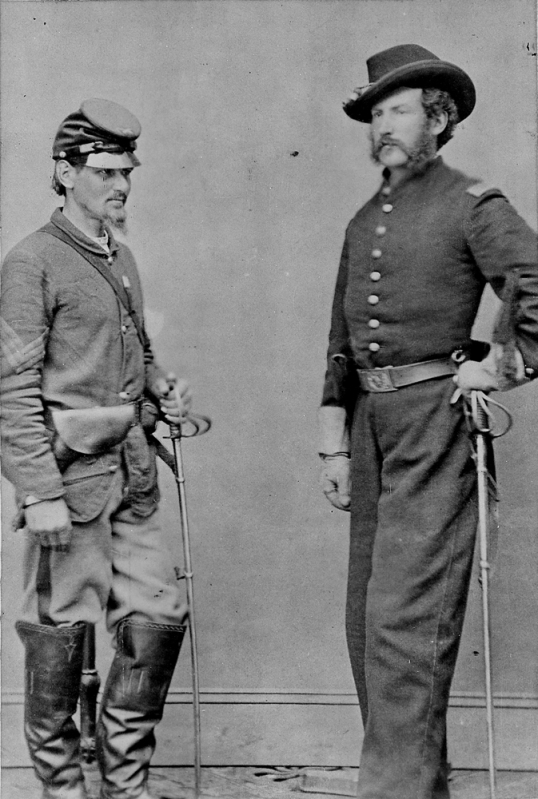

Boston Corbett and Edward Doherty

The injury that has been done us by giving us a small share, instead of the principal share of the rewards, cannot now be remedied, since it has passed Congress in that way. But be assured, dear sir, that I stand ready to give a certificate at any time, properly attested if needs be, that I have ever known you to be a brave and efficient officer, and never in my life saw any act on your part that indicated cowardice in the least degree.

I always liked to go on a scout with you, because I knew you to go forward in the work, and a true officer and soldier, having the welfare of your command always in view, and losing no opportunity of doing good service for your country.

With kindest regards and earnest prayers for your welfare, and that you may outlive all such wicked slanders, I remain, as ever

Boston Corbett”

As grateful as Doherty must have been for Corbett to come to his aid, Hotchkiss’ slanderous remarks apparently continued to gnaw at the lieutenant. Over three months later, on November 26th, Doherty wrote another letter to Corbett seemingly asking the late sergeant to write out a more thorough or perhaps notarized affidavit regarding Doherty’s services in apprehending Booth. It is Boston Corbett’s letter to Doherty’s second communique, months after the Hotchkiss affair, that is housed in The Durham Museum in Omaha.

Even though Corbett had written in August of 1866 that he stood ready, “to give a certificate at any time, properly attested if needs be,” regarding Doherty’s actions and character, in this response to his former commander in December of 1866, it appears that Corbett is trying to get Doherty to put the whole incident aside.

91 Attorney St

New York

Dec 1st 1866Lieut E. P. Doherty

Dear Sir

Your letter of Nov 26th reached me yesterday. And as I was not sure by the heading of it wether [sic] it meant South Carolina, or Lower Canada; I concluded to write to you for the Address in full; And also to suggest that it might be best to drop the whole matter; And let it end as it is.

For my own part as a Christian I freely forgive Mr. Hotchkiss for the injury that he has done; And so would rather let end thus. But if you still insist upon the Affidavit being made to clear your character, I feel that I owe it to you to do it. And so would not further refuse.

But while I sincerely desire to see your Character Vindicated: how much rather would I see your soul saved, And you brought to love and serve God with all your heart. I expect you think it very strange that I appear so indifferent to that which is a point of honor; but the secret of it all is this the Christian knows that the time will soon come when the secrets of all hearts will be made bare in the judgement And he feels that he can well afford to be hid about here. So that he stands justified there. This with me is the only cause of reluctance to make the Affidavit, which I believe I can do with a clear conscience if you think best after reading this.

If you have written me lately before; the letter never reached me, for the only letter that I have got from you before this since you have been in the Service again; was dated Sumter, S.C. August 1st. Which I promptly answered

Will you please inform me if you have taken any steps to get the Local Rewards collected. When I was in Washington to get the Amount that Congress Awarded me, I went to Johnson, Brown & Co, at the Intelligencer Building and put my interest in their [sic] hands to collect for me. They advised me to consult with you, which I fully intended doing before, but rather expected to hear from you. They have written to the Pennsylvania Govt. and received Answer by Official Document which I have. That this Reward was on condition that Booth be taken in the State.

With kindest regards Boston Corbett

Please direct to 91 Attorney St. Mr. Peck is out of Business now and no longer holds the store where I was working.

Boston Corbett was a deeply devoted Christian almost to the point of being a zealot (the man castrated himself in order to avoid the temptations of the flesh, after all). While his preaching helped to bring hope to his fellow prisoners at the Andersonville prisoner of war camp during the war, I highly doubt Lieut. Doherty was pleased to find that Corbett had responded to his request for help with a lesson on Christian forgiveness.

After side-stepping the issue of Hotchkiss with his talk of saving Doherty’s soul, Corbett then went into a topic he knew would be of mutual interest to them both: more reward money. While both of them had received their share of the reward money offered by the federal government, Corbett mentioned his attempt to procure some of the smaller rewards that certain states and cities were offering after the assassination of Lincoln. He apparently made application in Pennsylvania for a reward they had offered, only to learn that the reward was contingent on the fact that Booth was actually found in Pennsylvania.

Coincidentally, Doherty was pursuing the same type of course with a reward that had been offered in D.C.. It’s possible that Doherty’s renewed desire to get an affidavit from Corbett was not just to seek vindication against Hotchkiss, but was designed to strengthen his bid for this local reward. Doherty certainly did not want to be maligned again as he sought a portion of the $20,000 the city of Washington had offered. This is especially true since most of the major players from the federal rewards case sought out their own share of the D.C. rewards as well.

For the D.C. money, Doherty was once again up against General Baker, Everton Conger, and Luther Baker. But the other claimants quickly grew as the case went through the courts. Washington was not as willing to pay out their reward and so the legal process lasted years. Lieutenant Doherty had submitted his claim in November of 1866, and by September of 1870, the case was still unresolved. By that time the number of claimants had swelled to 39, and rather than fighting with each other over who should get what amount, they were all working together to force D.C. to pay out the money they had promised. In the end, however, their case was dismissed when the judge determined that the city of Washington, funded by Congress, never had the authority to offer the $20,000 reward in the first place. The only legitimate reward the claimants could have hoped for in the city of Washington was the federal one which had been paid out in 1866.

This letter by Boston Corbett provides a new look into the unique mind of the man who avenged Abraham Lincoln. It is also a great artifact for teaching about the drama and intrigue that was involved in the avengers’ quest for reward money. I’m thankful to The Durham Museum for sharing it with us. It never hurts to ask a museum what they might have hiding in their collections. As shown from this letter, the results can be pretty interesting.

References:

The Byron Reed collection at The Durham Museum

Steven G. Miller

The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of First Session of the 39th Congress

The Lincoln Archives Digital Project

Genealogybank.com

The Omaha World-Herald

Really enjoyed Boothie Barn.

Thanks

As always, I highly Commend you for the rarely seen photographs you put in your blogs!

Great find Dave! Does the museum give a provenance?