After I posted about the update to the Maps section yesterday, Lincoln researcher Eva Lennartz of Germany made the following comment:

“I have a question – from Mr. Fazio’s new book I just “learned” Surratt’s leap over the balustrade was an embellishment (which would make sense to me). So you think it wasn’t?”

What follows is my response to Eva, which started as a comment but quickly grew into a post.

Eva,

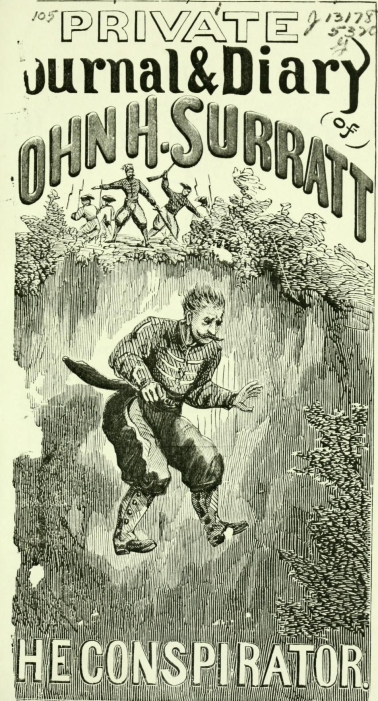

With regards to John Surratt’s leap from justice on November 8, 1866, there has been some embellishment done to the story (particularly in some of the fanciful penny dreadfuls, that illustrate this post), but records are clear that he did make the jump.

You’ll remember that John Surratt was most likely in Elmira, NY when the assassination occurred. When he heard the news he fled up to Canada, where he was hidden away for the entirety of the trial of the conspirators. In September of 1865, Surratt traveled from Montreal to Liverpool, England. From there he made his way to Rome where he enlisted in the Papal Zouaves (the Pope’s army) on December 11, 1865. His alias was John Watson, a native of Scotland and he served in the Papal Zouaves until he was identified by a fellow zouave, Henri Beaumont de Ste. Marie. Finally, on November 7, 1866, John Surratt was arrested by the Zouaves on the request of the American government and imprisoned for a night in the Zouave barracks in Veroli, then part of the Papal States. On the morning of November 8th, Surratt was awaken by the guards, told he was going to be transported to Rome, given coffee and then marched with a guard of six men towards the barracks gate. As the story goes, before reaching the gate John Surratt asked to use the privy which was located near the back of the barracks and overlooked a cliff leading down to the valley below. He was given permission to use the privy and, upon being unescorted near the latrine, he vaulted over a balustrade and leapt over the cliff. Let’s look at the reports and accounts of John Surratt’s escape.

Right after Surratt made the leap and escaped, the commander of the detachment in Veroli, Captain de Lambilly, sent a telegram to Velletri that was forwarded on to Rome. It said, “At the moment he left the prison, surrounded by six men as guards, Watson plunged into the ravine, more than a hundred feet deep, which defends the prison. Fifty zouaves are in pursuit.”

Later that day, when the pursuit of Surratt had failed to recapture him, Captain de Lambilly, would write about the circumstances further. “The gate of the prison opens on a platform which overlooks the country; a balustrade prevents promenaders from tumbling on the rocks, situated at least thirty-five feet below the windows of the prison…This perilous leap was, however, to be taken, to be crowned with success. In fact, Watson, who seemed quiet, seized the balustrade, made a leap, and cast himself into the void, falling on the uneven rocks, where he might have broken his bones a thousand times, and gained the depths of the valley”.

Probably the most helpful account, however, is one written by Colonel Allet, De Jambilly’s immediate superior. Allet was stationed in Velletri, some 70 km away from Veroli. After Surratt’s escape on November 8th he sent one of his men to Veroli to investigate. On November 9th, Allet wrote to his superior, the Pontifical Minister of War, what had been learned from the investigation: “I am assured the escape of Watson savors a prodigy. He leaped from height of twenty-three feet on a very narrow rock, beyond of which is a precipice. The filth from the barracks accumulated on the rock, and in this manner the wall of Watson was broken. Had he leaped a little further he would have fallen into the abyss.”

From the above records it seems a bit unclear the exact distance of Surratt’s leap. Regardless, there’s no doubt that Surratt made this perilous leap and was extremely lucky to have landed where he did. Had he missed the outcropping of filth covered rocks some 23 – 35 feet below, he surely would have perished in the fall. But that’s not to say that even the jump he made couldn’t have killed him. Even Captain de Jambilly was astonished that Surratt survived, “Lieutenant Monsley and I have examined the localities, and we asked ourselves how one could make such leaps without breaking arms and legs.”

Despite what Mr. Fazio might have you believe in his book, John Surratt did not land unscathed. He injured his arm and his back in the fall. That is why, when he reached the Italian city of Sora, Surratt sought medical treatment. From Sora he went to Naples where he was questioned and held by the authorities there. While there he passed himself off as a Canadian and told the Naples police that, “he had been in Rome ten months; that, being out of money, he enlisted in the Roman Zouaves, &c.; that he was put in prison for insubordination, from which he escaped, jumping from a window or high wall, in doing which he hurt his back and arm, both of which were injured.”

So, let’s look at the evidence. In supporting John Surratt’s leap we have multiple 1866 reports on the nature of his escape, and a supporting confession from John Surratt himself before any publication of the story occurred. On the side against him making the leap is a newspaper article from 1881 filled with the inaccuracies. You can read Mr. Lipman’s account for yourself HERE.

The account is filled with errors, but the one that makes it the most obvious that Lipman never met Surratt in the Zouaves is the fact that he gives the precise year of 1867 as when everything occurred. As we know, Surratt was back in America in 1867 as he was standing trial by then. Lipman shows some knowledge of the Italian territory (though his geography of Surratt’s whereabouts doesn’t exactly match the official record) which makes it possible that he could have been a member of the Zouaves himself. However, it seems that, after learning the details of John Surratt’s arrest from other zoauves or even just from the latter’s highly publicized trial, Lipman decided, years later, to falsely add himself to the narrative.

Is the story of John Surratt leaping over the balustrade at the Papal barracks in Veroil, Italy a dramatic one that is hard to believe? Absolutely, but it did happen.

Surratt had be on the run for over a year and a half before he was his arrested in Veroli. Did he plan his perilous escape while sitting in his cell the night before or did the idea just come to him as he walked near the barracks’ privy? Did Surratt take the plunge expecting to die in the attempt, or did he have faith he would live? How did his survival from such a death defying leap affect the rest of his escape and his life? These are the fascinating questions that I like to ponder.

I hope this helps, Eva. Remember to always question noncontemporary sources from people claiming to have been involved in historical events. The desire to be connected in someway to history can drive even the most decent and honest person to lie and exaggerate. Too often, authors are so determined to find proof of their claims that they suffer from confirmation bias, and put their faith in disreputable sources like these in order to “prove” their beliefs.

I would, however, be remiss if I did not include this final note on the subject. On April 8, 1867, a newspaper article was published in the New York Times entitled, “A Visit to Surratt”. The article recounts the visit of the newspaper corespondent to John Surratt’s jail cell, where the conspirator permitted an interview. You can read the full article HERE.

According to the article, while John Surratt was in prison in America he read, “with great apparent interest, the published accounts of his capture and escape.” The article then recounted the following regarding his famous leap:

So perhaps, Surratt’s magnificent jump was only a distance of twelve feet. By the time the other zouaves made it over to the balustrade and looked down he could have climbed down the extra ten or fifteen feet, which was then thought by those above to have been the distance he fell. We don’t know for sure. What we do know is that John Harrison Surratt did continue his flight from justice by taking a leap of faith in Veroli, Italy, only to be captured less than twenty days later, in Alexandria, Egypt.

References:

The Pursuit & Arrest of John H. Surratt: Despatches from the Official Record of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln edited by Mark Wilson Seymour

John Surratt: The Lincoln Assassin Who Got Away by Michael Schein

GREAT reply and pictures, Dave!!! Many thanks – I’ve always wanted to know more about this incident!!! Thanks again!

Thank you, Eva, for the inspiration!

Thank you so much for once again reiterating the facts about John Surratt’s dramatic escape. I must admit that “revisionist” history on many of the Lincoln assassination aspects is wearing this old lady down!

I should also have mentioned below that I’m glad you used Michael Schein’s work as a reference. JOHN SURRATT: THE LINCOLN ASSASSIN WHO GOT AWAY is a very good book and an easy historical read. His version of “The Leap of Legend,” as the chapter on Surratt’s escape from Italy is named, is especially informative and well documented. Included in the book is a photograph taken of the precipice from which Surratt jumped as it appears today. Mr. Schein visited Italy during his research for the book.

I’m very much enjoying Mr. Schein’s book on John Surratt. You can tell he has done his research and has shifted through everything to determine the truth (near as we can tell). I highly recommend the book.

Never knew about the leap Truth is stranger than fiction

It certainly is, Russ.

Dave:

I have prepared a response to your post on John Surratt. It is not composed yet, so I’m not sure how long it will be; probably about three pages. How would you like it –as a comment; as an email; or as an attachment?

John

How you want to respond is entirely up to, John. I would recommend it be a comment though, so others might read it.

Dave:

I am trying to send you a reply to your most recent message (recommending a comment), but after I type in my reply, the site does not give me the facility to post it. What am I doing wrong? I sent the earlier message without difficulty.

John

Dave (and Eva, Laurie and Russ, too):

Dave, I commend you on a fine piece of scholarship, a skill for which I have great admiration. My only regret is that you came to the wrong conclusion, which is O.K., because “the credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena”, and I don’t know anyone in this business, with the possible exception of Laurie, who is more in the arena than you , or anyone who, even when he fails, does so with greater daring. So, my hat is off to you.

Recognizing that certainty with respect to this issue (and so many others) is not obtainable, and that possibilities are infinite, we must once again content ourselves with probabilities. In my judgment, the probabilities are that Surratt escaped through a sewer with the complicity of his Zouave guards, who were his comrades, that they lied to cover up their complicity and to avoid a charge of gross incompetence and dereliction of duty, that their immediate superior (Lt. de Monsty) also lied for the same reasons, that Surratt lied to protect his comrades, that many who were not privy to the truth simply repeated the lie in ignorance, and that Henry Lipman, one of Surratt’s Zouave comrades who had participated in the event, told the truth when it was safe for him to do so. Because the lie was repeated so often and by so many, and because it is a largely an academic question (i.e. few besides scholars and historians care how Surratt escaped), the lie took root and to this day is accepted as truth by some authors, students of the assassination, etc., but fortunately not by all: Jampoler and Pitch, for example, are two who have recognized the flimflam for the falsehood it is. I come to these conclusions using the tools that I always use, namely evidence (eyewitness, material and circumstantial), reason and an understanding of human nature.

Surratt’s work as a Secret Service agent required that he lie often and well. He therefore became expert at it. He told at least three different versions of his activities from April 4 through April 18, 1865, for example (four if we include Ste. Marie’s testimony placing him in Washington on the 14th), and at least two different versions of his alleged leap. The lies in his Rockville lecture, in his Hanson Hiss interview, and in statements made by him and recorded by others, are so palpable they fairly leap off the page. We should expect the truth from him, therefore, only when he has absolutely no interest in lying and perhaps not even then.

Further, it is common knowledge that men in arms bond with each other strongly because they share a common ordeal and have a common enemy. They endure the same grueling training, wear the same uniform, shoulder the same arms and embrace the same cause. We have all heard about bands of brothers, buddies and having each other’s back. So it was with the Papal Zouaves. Easy to understand. “Watson” (Surratt) was therefore more than a soldier, he was a brother, a buddy, a comrade-in-arms, whose back was had by his fellow Zouaves. Call it a Musketeer mentality: All for one and one for all! We pick up some of this in the interview of Surratt that appeared in the New York Times on April 8, 1867, which you kindly furnished your readers. In it, Surratt speaks of having had information of Ste. Marie’s “treachery” before it was finally accomplished, and of being advised from time to time of the steps taken to secure his arrest. He also mentions “arrangements” he had made for desertion and flight being nearly perfected at the time of his arrest. Such information could not have come to him and such arrangements could not have been made, obviously, without informers and accomplices.

Now, with the foregoing in mind (Surratt is a chronic liar and his fellow Musketeers will do whatever they have to do to save him), let us consider the evidence. Note that Surratt did not mention his leap in his Rockville lecture, a lecture otherwise filled with self-serving puffery and descriptions of his derring-do. It is entirely possible that he left it out, indeed left out all mention of his experiences as a Zouave , because Henry Lipman was in the audience, or at least so said Lipman, who added that Surratt “singled (him) out among the audience and embraced (him) with gratitude”. Surratt couldn’t very well tell a “leap” story in the presence of one who knew it wasn’t true and who, in fact, had participated in the real escape, for which Surratt expressed his gratitude. Surratt did, however, speak of the leap in his Hanson Hiss interview, given 28 years later when there was no one around to call him on it. There he described how he, spontaneously, without prior arrangement, bolted from his guards, who are not said to have been in any way disposed to help him, ran across a court-yard, jumped on a wall and then, with his legs doubled under him, leaped into a ravine which was more than 100 feet deep! Note that nothing is said about Surratt asking to use the privy and then using the privy for the purpose of accessing the balustrade that overlooked the ravine. But, Lo!, there was a “bare ledge of rock jutting out from the face of the mountain, 35 feet below and about four feet wide, upon which, “by great good fortune”, he landed safely. Note that nothing is said about the ledge being a depository for barracks filth, but, on the contrary, the ledge is expressly described as “bare”. The odds against one landing safely on a four-foot outcropping of rock after a drop of 35 feet are probably near zero, but we will pass over that , because what follows is pure yarn telling, sufficient to establish that Surratt is blowing hot air again: Didn’t he know of the existence of the ledge? “Know of it? Why, of course I knew of it…”, followed by a description of how his guards fired down on him from the top, all of them (at least six) firing at a stationary Surratt 35 feet below and all missing him!! “Shaken” he made his escape, first finding refuge with his enemies (the Garabaldians), then making his way to Alexandria, nothing said about needing, seeking or receiving medical attention. Even if he did receive medical attention, at Sora or elsewhere, there is no reason to suppose he needed it for injuries sustained at the ravine; it could have been for injuries he sustained elsewhere. In his April 8, 1867, New York Times interview, he speaks of many physical ordeals he experienced in his flight, such as sliding down a 100-foot declivity on his back. C’mon Dave; you’re among friends. You don’t believe this story any more than I do. A man landing on a rocky ledge after a fall of 35 feet, with or without his legs tucked under him and with or without barracks filth on it, would be killed. Period. Ipso facto. The compression injury to his spine would shatter it, killing him instantly. The story is completely unbelievable, senseless, absurd, contrary to reason, from start to finish.

Captain de Lambilly’s report confirms that the distance from the top of the ravine to the ledge (“the rocks”) is indeed 35 feet, adding that the rocks were uneven and that Surratt “might have broken his bones a thousand times”. But the Captain’s confirmation of the leap, of course, is merely a repeat of the story given to him by the guards and de Monsty and is therefore only as accurate as their story, which, as just said, is completely contrary to reason and therefore unbelievable, a fact unintentionally confirmed by de Lambilly by his reference to uneven rocks and broken bones and also by his saying that he and de Monsty examined the localities and asked themselves how one could make such leaps without breaking arms and legs. The answer, of course, is that one could not.

Colonel Allet’s report suffers from the same weakness: it merely repeats the unbelievable story told by the guards and de Monsty and repeated by de Lambilly, plus the results of an investigation by one man, who must surely have been told, and therefore repeated, the same yarn told by the guards, de Monsty and de Lambilly. Allet’s report, however, fixes the distance from the top of the ravine to the ledge at 23 feet and does mention barracks filth. These items, however, do not affect the result—a fall from such a height would still result in death or at least very serious injury—but do demonstrate that there was falsification of the facts from the very beginning, by the guards and de Monsty.

But we are not finished yet, because Surratt, in his New York Times interview, alludes to the leap story as a source of great amusement to him and fixes the actual height of the leap at 12 feet (!), again demonstrating gross falsification of the story from its very inception in 1866 and also demonstrating the incredibly poor marksmanship of the six or so guards who fired down upon but could not hit a stationary Surratt 12 feet below them! No wonder they lost the war.

We bear witness, therefore, to the creation of a myth, which, like so many others, has been repeated so often that it now passes as history. It even found its way into Surratt’s trial (Vol. 1, p. 119; Vol. 2, p. 1257) and, of course, into the books of many well-meaning authors and the works of other Civil War enthusiasts, especially students of the assassination.

The corrective came on February 21, 1881, in the form of a New York Times account of an interview of Henry Lipman, who claimed to have been a Papal Zouave with Surratt at the time of the latter’s escape. His narrative is sufficiently cohesive and accurate to conclude with near certainty that he was in fact a Zouave, but to remove any doubt, I have requested confirmation from the Vatican Library. Stay tuned. Dave, your characterization of Lipman’s account as “filled with errors” is an exaggeration, though there are some errors, none damaging the veracity of the story he tells and all of a kind one would expect in an account given 15 years after the fact. The most egregious error is his reference to 1867 as the year of the events rather than 1866—a harmless slip, easily made, because Surratt’s arrest occurred on November 7, 1866, a mere seven weeks from 1867, or perhaps a slip not made by him, but by the interviewer, the transcriber or the typesetter. The use of the wrong date had to be an accident, because it is a matter so easily confirmed or not confirmed. In any case, despite the erroneous date, Lipman’s story clearly has the ring of truth to it. It is a vastly more believable story of what happened than the leap story and one not cluttered with the inconsistences that expose the latter story as fraudulent. Dave, your conclusion that “…after learning the details of John Surratt’s arrest from other Zouaves or even just from the latter’s highly publicized trial, Lipman decided, years later, to falsely add himself to the story” is wide of the mark. Stop and think about it: Do you really believe that this laconic Dutchman, who spoke six languages fluently and understood Latin and Greek, who traveled in Europe, Asia, Africa and America, and who had taken part in several campaigns in both hemispheres, had nothing better to do with his time and energy that to add himself to a story which he had not been a part of, thereby making up an entirely new story out of whole cloth? And this with absolutely no motivation, because he had nothing to gain by lying, other than whatever publicity could be gained from one newspaper article, which one could probably put in a thimble and maybe sell for a buck. Contrast that with Surratt, who had every reason to lie, namely the protection of the dozen (not six) Musketeers who helped him escape, all 12 of whom were “tried friends of Watson”, according to Lipman. It all fits. The Musketeers, whose purpose it was to help their D’Artagnan escape, would not escort him to a 100-foot ravine for a leap, where he would almost certainly be killed or at least very seriously injured even if he managed the nearly impossible feat of landing on a 4-foot wide ledge after a 35-foot or 23-foot plunge. They would, rather, seek a much safer way to accomplish their purpose, such as having D’Artagnan negotiate a concealed sewer into a rivulet, which would be followed by “a furious fusillade on our part, its object being naturally to divest suspicion and to make believe that we were trying to stop the fugitive”. The execution of the plan seems to have earned the admiration of de Monsty (doubtless in on the whole charade), who smiled knowingly and approvingly when told of the escape, secretly rejoicing in the same, according to Lipman, a detail that also has the ring of truth because it is totally gratuitous, serving Lipman in no way.

In conclusion, we may say with near certainty that the story of Surratt’s escape by leaping into a ravine was fabricated by his “guards”, who were actually his comrades and who were determined to save him from deportation to a Godless country and prosecution there for alleged complicity in the assassination of the American President. With some inconsistencies, the fabricated story was accepted by the guards’ officers as true and therefore found its way into their reports, despite its improbabilities, and accepted thereafter by just about everyone else, until 1881, when a different account of the escape was given by a Zouave who participated in it, who therefore knew the truth and who had no motivation to lie. Surratt continued to affirm the earlier, fabricated version of the event as a way of protecting his comrades, though on at least one occasion he partially let his guard down by saying that he was amused by the fabricated story and all that had been made of it and that the height of the leap wasn’t really 35 feet or even 23 feet, but 12 feet. He apparently made this statement because he realized that the 35-feet and 23-feet versions of the story were simply unbelievable, but in so doing he clearly demonstrated that the guards’ original version of the event was hokum.

John

Sources: Anthony Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead”

C. A. Jampoler, The Last Lincoln Conspirator

Louis J. Weichmann, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

New York Times, April 8, 1867

New York Tribune, February 21, 1881

Washington Post, April 3, 1898

Daily National Intelligencer, March 25, 1867

The Vatican Library (pending)

In my just published biography of John Surratt, Jr., I do, of course, discuss the escape, both versions. Having read both and considered the likelihood of one or the other, I believe that Lipman’s story is nearer to the truth than the sensational leap over the wall into a pile of poop. We cannot trust Surratt’s telling of the story, for his accounts are inconsistent with one another, and they are self-serving. John Surratt told many tall tales about his life, and while we must pay attention to what he said, we should not believe him any more than we might believe some one else. Also, accounts of those who got their information mainly from Surratt should be suspect. There are clues in Lipman’s version which point to his being sincere. He describes the prison in detail, he refers to other guards by name, he describes Surratt, claiming several conversations with him, none of which are inconsistent with known facts. While it is true that his account appeared after some time (1881), that does not mean that he made the whole thing up. Since we are dealing with two versions of the same story, we cannot say that one must be all right and the other all wrong. Testimony which pits one witness against another, with no further evidence from a source not involved, must be judged at face value. We must then depend on our ability to ask ourselves which version sounds more like the truth? Lipman mentions that he, and the other guards, were punished for letting Surratt escape. He suggests that the officer inflicting that punishment, appeared to have a knowing smile, indicating that he secretly approved of their letting the prisoner escape. Comparing the two stories, it would throw much more blame on the guards if they had a role in helping Surratt to escape. Guards, even if standing close to him, could easily miss catching him as he jumped over the wall, whereas if he climbed into a drainpipe, which had been shown to him by the guards, suspicion would be cast on those guards, who would probably have been punished much more severely than simply having to spend a night in the prison, themselves. If it is true that Surratt was injured in escaping, we cannot know with certainty what was the extent of those injuries, nor can we directly connect them with jumping over the cliff. There are many places in the story of the life of Surratt where we must decide which version is true, or which is closer to the truth. Often, we will find that it cannot be determined with certainty. In my book, I have told the stories derived from Surratt himself, and his guards, as well as Lipman’s account. I believe Lipman’s is the more likely, but I leave it to the reader to decide. It is unlikely that we will ever find evidence which contradicts the generally known versions. Most likely, if such evidence does appear, it will be yet another version of the same story, with the same dilemma for us to choose which one seems most likely. Frederick Hatch

Thank you for your reply, Fred and I will be sure to pick up your book soon. I appreciate your thoughts on the matter yet I am still more likely to trust the words of the various officials who reported on Surratt’s escape right after it occurred that the later recollections of a man who contradicts them. In my view, the weight of proof still lies with a modest leap, the height of which was exaggerated to unbelievable levels, rather than an agreed upon conspiracy among the Papal Zouaves to help Surratt escape. Best, Dave