The following article was my very first foray into researching and writing about the Lincoln assassination story. It was originally published in the November 2010 issue of the Surratt Courier.

Emerick Hansell: The Forgotten Casualty

By Dave Taylor

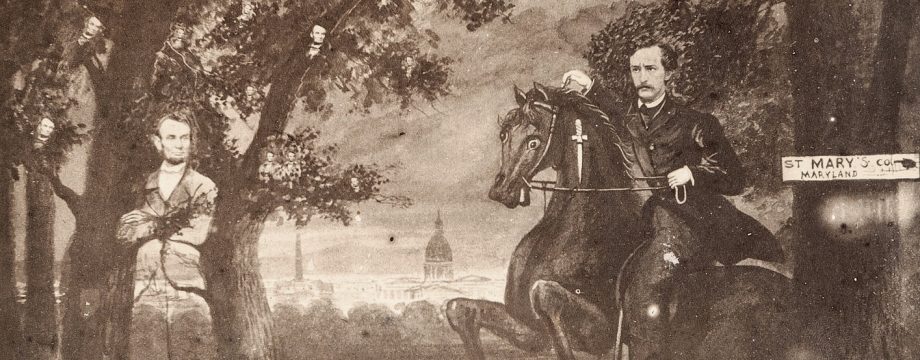

“I’m mad, I’m mad,” were the alleged words of the assassin Powell as he fled from the bloodied scene behind him. Assigned by John Wilkes Booth to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward at his home, Lewis Powell encountered a small resistant force that hindered the battle trained Confederate from completing his task. In his wake, Powell left a menagerie of wounds and wounded:

- Secretary Seward’s face was slashed, opened, and forever scarred by Powell’s blade.

- Frederick Seward, who was spared a bullet when Powell’s gun misfired, received, instead, a skull splitting slam from the butt of the insolent weapon.

- Private George Robinson, the newly assigned male nurse to the Secretary, endured stabs and blows while wrestling with the assailant.

- Augustus Seward joined Private Robinson in defense of his father and withstood similar swipes from Powell’s fists and knife.

- The last victim of that night, and the subject of this article, is an oft forgotten State Department messenger named Emerick Hansell.

Even in the most detailed of assassination texts, Hansell’s involvement that night is generally summed up with a variation of the following sentence: “As Powell, raced down the stairs of the Seward home, he met State Department messenger, Emerick Hansell, and stabbed him in the back.” With that, Emerick Hansell usually enters and leaves the pages of documented history. However, further research into Emerick Hansell’s past and future yields further connections to his actions on April 14th, 1865.

Emerick W. Hansell was born near Philadelphia in 1817. In 1840, he married D.C. native Elizabeth Ann Robinson and moved into the Capital. Together they had one son, George, and two daughters, Emma and Roberta. They also had one child who died in childbirth. This death would be the first of many sorrows in Hansell’s life. Hansell’s occupation prior to his government work is unknown, but by 1855 he was employed by the State Department as an “acting” messenger. For this position he was paid $700 a year.[1] By 1858, Hansell was a full messenger and made $900 a year, a pay rate he sustained throughout his tenure.[2] With the onset of the Civil War, the State Department inherited ever increasing duties. Later, Frederick Seward reflected on the department employees during wartime and stated that Hansell was a man, “of proved efficiency and integrity.”[3] Along with his government work, Hansell was a member of the International Order of Odd Fellows, a charitable fraternity. The Hall of Odd Fellows in D.C., a common meeting place for the Order, is also the same venue in which John H. Surratt Jr. was scheduled to appear during his post-trial lecture circuit.[4] Hansell was also an active member in St. Paul’s English Lutheran Church, attending and teaching adult Christian classes. By 1865, Hansell was a respected and integral employee of the State Department, ferrying messages between the department headquarters and the Secretary of State. On the night of April 14th, Hansell’s continued “efficiency and integrity” would be tested by Powell’s blade.

In the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, the coincidental stabbing of a messenger at Seward’s was unimportant and almost undocumented in the conspiracy trial. While Mr. Hansell’s name is included with the other wounded parties in the charges against Lewis Powell, his involvement in the affair is limited to the testimony of only one witness: Dr. Tullio S. Verdi.

Dr Tullio Verdi

When the call for doctors rang out following the massacre, Dr. T. S. Verdi was the first to arrive at the Seward home in Lafayette Park. As he recounted in an article a month later, “I found terror depicted on every countenance and blood everywhere.”[5] As the initial doctor present, Verdi began triage duty. He first saw to the Secretary. After announcing that the facial wound was not fatal and applying ice to stop the bleeding, he was told of Frederick’s condition. Dr. Verdi barely finished applying ice to Frederick’s hemorrhage when he was sent to tend to Augustus’ stabs. Initially, Dr. Verdi was shocked as the number of wounded increased only to have this shock eclipsed by growing terror. After seeing to Private Robinson’s wounds, he was called to see Emerick Hansell.

In the conspiracy trial transcript as compiled by T. B. Peterson & Brothers, Dr. Verdi’s account of Hansell’s wound is limited to a single sentence: “I found Mr. Hansell, a messenger of the State Department, lying on a bed, wounded by a cut in the side some two and a half inches deep.”[6]

Luckily, Benjamin Perley Poore’s transcript of the trial did not condense Dr. Verdi’s account: “I found Mr. Hansell in the south east corner, on the same floor with Mr. Seward, lying on a bed. He said he was wounded: I undressed him, and found a stab over the sixth rib, from the spine obliquely towards the right side. I put my fingers into the wound to see whether it had penetrated the lungs. I found that it had not; but I could put my fingers probably two and a half inches or three inches deep. Apparently there was no internal bleeding. The wound seemed to be an inch wide, so that the finger could be put in very easily and moved all around.” Dr. Verdi was then asked if the stab had the appearance of being just made to which he responded, “Yes, sir: it was bleeding then, very fresh to all appearances. Probably it was not fifteen or twenty minutes since the stab occurred.” [7]

While at the conspiracy trial Dr. Verdi asserted that the wound was not fatal, there must have been some uncertainty at the time. When Secretary of War Edwin Stanton arrived at the Secretary of State’s home, he found Seward, Frederick and Hansell each “weltering in their own gore.”[8] Later, as Stanton was attending to President Lincoln’s deathwatch, he sent a dispatch to Major-General Dix stating, among other things, that, “The attendant who was present [at Seward’s] was stabbed through the lungs, and is not expected to live.”[9] Contrary to Stanton’s dispatch, Hansell’s wound, like all those inflicted by Powell that night, proved to be non-fatal.

Dr. Verdi’s brief testimony contains the only official mentioning of Emerick Hansell in the conspiracy trial. While beneficial, it does little to explain Hansell’s presence and whether he had just arrived or was departing the scene when he was stabbed. Hansell, unlike Augustus Seward, Private Robinson, and doorman William Bell, was never called to testify about his experiences. Oddly enough, these men did not mention Hansell in their testimonies at all. This is surprising since it seems that someone had to have helped Hansell up the stairs and into the third floor bedroom where he was found by Dr. Verdi. These omissions led one author in the 1960’s to propose that Augustus Seward perjured himself on the stand and that it was actually Hansell who helped Robinson eject the assassin from the Secretary’s room[10]. However, further research disproves this theory.

During the trial for John H. Surratt Jr. in 1867, the prosecution recalled many of the same witnesses from the initial conspiracy trial. William Bell, Augustus Seward, and Private Robinson returned to give their accounts. The prosecution also brought in new witnesses: Frederick Seward and his wife Anna. Dr. Verdi was not recalled and Emerick Hansell was still absent. Nevertheless, in this trial, it is Private Robinson who recounts Mr. Hansell’s actions that night, “On [Powell’s] way down, on the first flight, he overtook Mr. Hansell, a messenger at the State department, who had been roused by the noise that had been made, and had apparently turned to go down stairs for help. He came within reach of him and struck him in the back.” Robinson was then asked if Hansell said anything to which he responded, “He started to say ‘O!’ I presume, but he did not say it exactly. He hallooed out pretty loud. He did not utter any particular word that I heard.” [11]

Pvt. George Foster Robinson

Robinson’s 1867 testimony is supported in a May of 1865 letter from Secretary Seward’s wife, Frances. In this letter she wrote, “While [Augustus] was stepping into his room for a pistol, the man made his escape down the stairs, on his way wounding Mr. Hansell, a messenger from the department, who came out of a lower room and was going to the street door to give the alarm.”[12]

From the above witnesses, we can conclude that Hansell had taken up residence in the Seward home the night of the 14th and was awakened by the commotion upstairs. As he left his room to either flee or raise the alarm, Powell overtook him and stabbed him callously in the back. It was a long and deep cut that barely missed penetrating his lungs. Then, someone in or around the Seward house helped the wounded Hansell up the stairs and into a third floor bedroom.

The bedroom he was placed in was Fanny Seward’s, the Secretary’s treasured daughter. In her diary Fanny wrote, “I went across the hall into my own room. I was there twice. The first time they were dressing poor Hansell’s back (he was stabbed in the back) the second time he lay on the bed. Eliza the seamstress was there to attend to him.”[13]

Lastly, Dr. Verdi, in an article published in May of 1865, gave the same basic story as the others with a slight change in where Hansell was sleeping and with an assumption about Emerick Hansell’s character. All emphases are Dr. Verdi’s: “Mr. Ansel (sic), the fifth person who was wounded, is a messenger in the State Department, and was sleeping that night over the Secretary’s room, waiting for his turn of watching. Hearing the fearful screams of Miss Fanny, he (a very weak-kneed gentleman) was making his way out of the house as fast as possible, when, after having descended a flight of stairs, he met the murderer, also on the landing. Mr. Ansel, however, endeavored to run faster; but the assassin, fearing he might give the alarm, gave him a memento of his brutality by plunging the dagger in his back.”[14]

Dr. Verdi’s description of Hansell as a “weak-kneed” gentleman may explain why Hansell was never called to testify and is barely mentioned in the trial testimonies. In contrast to the brave Private Robinson who fought off the assassin, Hansell was running away when he was stabbed. His assumed cowardice made it so very little was said about his role that night. When the media did report on him and his recovery, the matter in which he received his wound was generally left out, as this excerpt from the April 18th New York Times will show: “Mr. Hansell, the Messenger of the State Department who was stabbed in the back at the same time, is a great sufferer, but believed to be out of danger.”[15]

Emerick Hansell would be in pain for the rest of his life. Following some time to convalesce, Hansell managed to return to his duties as a messenger and faithfully continued to carry them out. Records show that he was still a messenger of the State Department in 1869.[16] In 1870, however, tragedy stuck Emerick Hansell again. On October 8th, 1870, Emerick Hansell’s wife of thirty years, Elizabeth, died of tuberculosis.[17] The loss of his wife, along with the ever growing pain from his wound caused Emerick to retire from the State Department at the age of 56.

Nothing is known about Emerick Hansell’s life for the next three years following his wife’s death. Some time during that period however, he must have been introduced to Mary E. Cross, a widow. Though twenty years his younger, the two courted and on June 4th, 1873, Emerick and Mary were married. Also during this period, a congressional action honoring Private Robinson for his bravery occurred. In 1871, for saving the life of Secretary Seward, Private Robinson was presented a Congressional Gold Medal and awarded the sum of $5,000.

The Congressional medal awarded to Pvt. George Foster Robinson for protecting Secretary William Seward.

By 1874, Hansell had been in constant pain for almost ten years. He elicited the help of Dr. Verdi and his own physician, Dr. Sonnenschmidt, to write letters on his behalf explaining the nature of his wound and its impact on his physical being. Dr. Verdi wrote back confirming that, “The wound is at present in such a condition as will preclude ever after his engaging in any active work for any length of time.”[18] Hansell’s reasoning for such confirmations of his condition? He was appealing the Congress to grant him a federal pension for his sustained wounds.

By 1876, the House of Representatives Committee of Claims had reviewed Hansell’s petition for a pension. Previous to this petition, federal pensions were limited to those who served the government in times of war in the Army or Navy. Except for the recent federal judiciary pension list, no civilians were granted pensions. Nevertheless, the Committee of Claims granted Mr. Hansell’s request. They justified their decision thusly:

“Mr. Hansell is now advanced in years, infirm, and disabled, as stated. In the opinion of the committee he is entitled to the just and generous consideration of the Government, and the most appropriate form of relief is that adopted toward those who have honorably served the country in the common defense and been disabled in its service. They therefore recommend that the name of the petitioner be placed upon the pension roll at the rate of $8 per month, to date from the 14th day of April, 1865, and submit a bill to that effect, with the recommendation that it pass.”[19]

While Hansell did not serve in the Army or Navy, the committee construed his actions on the 14th as being in defense of Secretary Seward, and therefore in defense of the country. His petition was transformed into “A bill (H. R. 3184) granting a pension to Emerick W. Hansell”. Upon reaching the House of Representatives, the bill was passed, and he was put on the pension roll.

Emerick Hansell’s signature

Then the bill was looked at by the Senate’s Committee on Pensions who were concerned about the precedent this bill would set. They challenged the House’s Committee of Claim’s justification for giving the civilian Hansell a pension. However, they did not disagree with granting him some money for his pain and suffering. The Senate, therefore, proposed, in lieu of a pension, the following amendment:

“That the Secretary of the Treasury be, and hereby is, authorized and directed to pay to Emerick W. Hansell, of the city of Washington, in the District of Columbia, out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, the sum of $2,000, on account of injuries received by said Hansell while in attendance upon the late William H. Seward, former Secretary of State, on the occasion of the attempted assassination of said Seward”[20]

This amendment was approved. A small debate then occurred when Senator Henry Anthony of Rhode Island proposed an amendment that would increase the amount from $2,000 to $5,000. Senator Anthony supported his amendment thusly:

“I should like very much to have the amount in the bill increased to $5,000. I think it is a great shame that this Government did not pay the expenses of the sickness, slow recovery, and surgical treatment of the illustrious Secretary of State and all others who were injured in that attempt at assassination which sent a thrill of horror throughout every part of the country, the South as well as the North. I should very much like, if it will not interfere with the bill and if my friend from Iowa will accept it, to amend it so as to give him $5,000, which I think is a very small compensation for the injuries which this faithful man suffered and which have disabled him for the whole of his future life.”

Many of the Senators asked for more information about Hansell, his injury, and his age. Unfortunately, their only source of information was the report from the Committee of Claims based on Hansell’s petition which, assumedly, was less than specific. One Senator, John Ingalls of Kansas, expressed his disagreement to the proposed increase fairly eloquently:

“I am aware that it is a very ungracious thing and a very difficult thing to attempt to argue against a sentiment, to resist an appeal that is made upon the ground of sympathy. So far as Mr. Hansell is concerned, of course no Senator here desires to say that he shall not be remunerated; but it seems to me that we ought not to give any more than he has asked; inasmuch as he himself has asked for but $8 a month, I can conceive that no good will be obtained by doubling the sum…”[21]

In the end, Senator Anthony withdrew his amendment. The new bill, granting Hansell $2,000 was renamed “A bill (H.R. 3184) for the relief of Emerick Hansell” and passed the Senate. It was then sent back to the House for concurrence, where Representative William Holman of Indiana recited his approval of the amendment thusly:

“I want to say a single word. I do not object to this, but I think the amendments made by the Senate are very wise and prudent amendments. Although this is an entire gratuity, it is one of those gratuities, perhaps, which are proper for the Government to give…”[22]

The House concurred with the amendments of the bill and it was signed by the Presidents pro tempore of both the House and Senate. President Ulysses S. Grant approved and signed the finished act on August 15th, 1876. Emerick Hansell was given $2,000 for the wound he received on the night of April 14th, 1865.

While many of the Senators spoke of Emerick Hansell’s advanced age, he was only 59 when his petition was granted. Though indeed infirmed, Emerick Hansell would live for seventeen more years after receiving his relief money. His actions during this time are unknown except that he continued to be active in both the International Order of Odd Fellows and in St. Paul’s English Lutheran Church.

At six o’clock in the morning on February 14th, 1893, Emerick Hansell died at the age of 75.[23] His death certificate lists “loco-motor ataxia” as his cause of death. In addition, he had experienced partial paralysis for several years as a result of his wound. In his will, Emerick left one dollar to each of his children and fifty dollars to St. Paul’s English Lutheran Church. The rest of his estate was left to his wife, Mary.[24] His funeral was enacted under the charge of the Odd Fellows.

Emerick Hansell’s final resting place is in D.C.’s Congressional Cemetery. There, he is buried next to his first wife, Elizabeth, who preceded him in death twenty-three years earlier. His gravestone bears the following epitaph:

“Emerick W. Hansell

1817-1893

Wounded with Hon. Wm. H. Seward, Sec. of State

By the Assassin Payne, April 14, 1865.

Erected by his Grandson Marvin Emerick Eldridge”

While Emerick Hansell’s actions on April 14th, 1865 could be debated as either cowardly or valiant, the wound he sustained; the one that infirmed him for the remainder of his life, should be looked upon with sympathy. His wound personified the savagery of the assassin Powell who deviated from his sole target of Secretary Seward, to attack and maim four others. For twenty-eight years after his death, Emerick Hansell continued to feel Lewis Powell’s brutality in every breath and movement of his body. When the assassination slowly faded from public memory, people like Secretary Seward, Frederick Seward, Augustus Seward, Private Robinson and Emerick Hansell bore the scar it forever. It is due to this suffering and this constant reminder of our dark history, that Emerick Hansell was granted $2,000 from a repentant and forgetful government.

Sources:

[1] U.S. Department of State. (1855). Register of officers and agents, civil, military, and naval, in the service of the United States, on the thirtieth September, 1855. Washington City, DC: A. O. P. Nicholson. (pg. 2).

[2] U.S. House of Representatives. (1858). Reports of committees of the House of Representatives, made during the first session of the thirty-fifth Congress. Washington City, DC: James B. Steedman. (pg. 22).

[3] Seward, F. W. (1891). Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State. (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Derby and Miller. (pg. 633).

[4] Swanson, J. L. (2006). Manhunt: The twelve day chase for Lincoln’s killer. New York, NY: HarperCollins. (pg. 376).

[5] Verdi, T. S. (1865). Interesting correspondence – full particulars of the attempted assassination of the Hon. Secretary Seward, his family and attendants. The Western Homoeopathic Observer, 2(7), 81.

[6] Peterson, T. B. (Ed.), (1865). The trial of the assassins and conspirators at Washington City, D.C., May and June, 1865, for the murder of President Abraham Lincoln. Philadelphia, PA: T. B. Peterson & Brothers. (pg. 82).

[7] Poore, B. P. (Ed.), (1865). The conspiracy trial for the murder of the president, and the attempt to overthrow the government by the assassination of its principal officers. (Vol. 2). Boston, MA: J. E. Tilton and Company. (pgs. 100-101).

[8] Storey, M. (1930, April). Dickens, Stanton, Sumner, and Storey. The Atlantic Monthly, 145, 463-465.

[9] Kauffman, M. W. (2004). American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln conspiracies. New York, NY: Random House. (pg. 62).

[10] Shelton, V. (1965). Mask for treason: The Lincoln murder trial. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. (pgs. 126-129).

[11] (1867) Trial of John H. Surratt in criminal court for the District of Columbia. (Vol. 1). Washington City, DC: Government Printing Office. (pg. 263).

[12] Seward, F. W. (1891). Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State. (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Derby and Miller. (pg. 279).

[13] Johnson, P. C. (1963). Sensitivity and Civil War: The Selected Diaries and Papers, 1858-1866, of Frances Adeline (Fanny) Seward. Retrieved from http://www.lib.rochester.edu/index.cfm?page=1420&Print=436

[14] Verdi, Interesting, pg. 85.

[15] (1865, April 18). The assassination… The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1865/04/18/news/assassination-condition-secretary-seward-improving-new-facts-about-murderers.html

[16] U.S. Department of State. (1869). Register of officers and agents, civil, military, and naval, in the service of the United States, on the thirtieth September, 1869. Washington City, DC: Government Printing Office. (pg. 2).

[17] (1870, October 9). Obituary – Hansell. The Philadelphia Ledger. Retrieved from http://www.congressionalcemetery.org/hansell-elizabeth

[18] House of Representatives. (1876). Index to reports of committees of the House of Representatives for the first session of the forty-fourth Congress, 1875-’76. (Vol. 2). Washington City, DC: Government Printing Office. (pg. 141).

[19] Ibid, pg. 142.

[20] U.S. Congress. (1876). Congressional record containing the proceedings and debates of the forty-fourth Congress, first session; also special session of the Senate. (Vol. 4). Washington City, DC: Government Printing Office. (pgs. 5059, 5060, 5080, 5659, 5663, 5683, 5689, 5698).

[21] Ibid, pg. 5059.

[22] Ibid, pg. 5683.

[23] (1893, February 14). Death of Emerick Hansell. The Evening Star. Retrieved from http://www.congressionalcemetery.org/sites/default/files/Obits_Hansell.pdf

*Note* This article, along with his death certificate, lists Hansell’s age as 74. However, basic math shows that Hansell, born sometime in 1817, would have to have been at least 75 when he died in February of 1893. If he was born in January or early February, he would have been 76 at the time of his death.

[24] Copies of Emerick Hansell’s last will and testament along with his death certificate were courteously provided by David Vancil of the Neff-Guttridge Collection at Indiana State University. The collection also contains a possible photograph of Mr. Hansell, though its provenance is disputed.

Recent Comments