As the writer of this blog, I have access to the visitor statistics. I can see how many people visit per day, what country they came from, what topics they read, and, entertainingly, what their Google searches were to get here. Most of the hits I receive through Google come from image searches rather than textual matches. For this reason, I try to include several pictures when I post. Looking at the searches today, I see that one visitor got here by searching for “photo of Lincoln’s 2nd inaugural address”. They found my blog through this search due to my new header image for the blog:

This image is actually a mix of two legitimate pictures of Lincoln’s second inauguration. I made it in Photoshop to place John Wilkes Booth in his correct place in the crowd, using the best image of him available.

There are several images of Lincoln’s inauguration, but only two (that I currently know of) clearly display John Wilkes Booth in the crowd. Websites (like Wikipedia) and institutions (like Ford’s Theatre) have incorrect displays of “Booth” at the inauguration due to the fact that they are using the best image of Lincoln, which is also the worst image of Booth. Before getting into all that, however, let’s discuss the history of these “Where’s Waldo?” photos.

From Booth’s own accounts we know that he was present at Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration. He later lamented to his friend, Samuel Knapp Chester, “What an excellent chance I had to kill the President, if I had wished, on inauguration-day.” While Booth was known for his hyperbole at times, the fact that he actually believed he could have killed Lincoln during such a highly attended event like the inauguration hints towards the fact that he must have been somewhat close to the President. Then in the February 13, 1956 issue of Life magazine, 90 year-old photography collector and historian Frederick Hill Meserve identified John Wilkes Booth in one of his pictures of the inauguration. In addition to Booth, Meserve also identified Mary Todd Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ward Hill Lamon, John T. Ford, and Lewis Powell. Now Meserve, as stated in the article, “spent 60 of his 90 years collecting photographs of the Civil War era,” and spent his whole life looking for and cataloging all the images of Lincoln that existed. He published his compendium with Carl Sandburg and called it, The Photographs of Abraham Lincoln. In his book, he included two different pictures of the inauguration. The first one, numbered 89, shows Lincoln seated before delivering his speech. Here is a scan of that image:

The second one, numbered 90 in Meserve’s book, is Lincoln standing and giving his speech:

This image is the most common photograph of Lincoln’s inauguration. In fact, practically every search for Lincoln’s second inauguration will provide you with his picture. Some websites even erroneously state that this is the only photograph of the event because it is used so exclusively. The reason for its exclusivity is because this is the best photograph of Lincoln. It shows the President addressing the assembled crowd in all his glory. Of all the images that were taken of the event, this one was the best.

The problem is while the above picture shows Lincoln at his finest, it does not fully show John Wilkes Booth. This is the reason why, in 1956, Meserve did not use this nice Lincoln picture to identify Booth. Rather, Meserve used another photo in his collection, one that he did not publish in his book, to make the identification. The image he used was not published because a fingerprint or smudge completely obliterated President Lincoln in it. Since Lincoln isn’t visible in the picture, it is rarely published or seen:

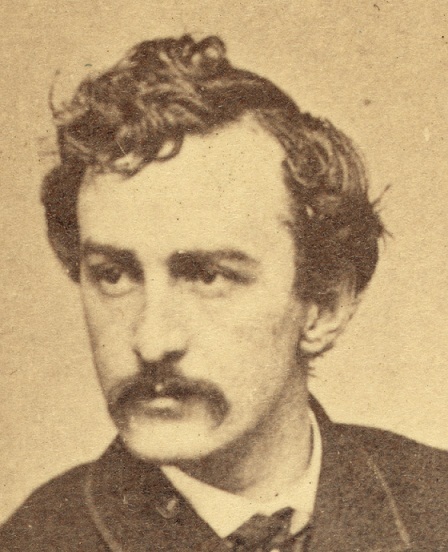

Using this picture however, Meserve identified Booth as being on the balcony wearing a tall silk hat:

This is the man identified by Meserve in 1956 as being John Wilkes Booth. Admittedly, there is no way to guarantee that this is Booth. Honestly, the man who discovered it in the first place was quite old when he published it for the first time. Nevertheless, the man Meserve identified does bear a similar appearance to the dapper, ivory skinned, mustachioed actor that would later assassinate the President. While it’s impossible to truly identify him as Booth, historians have accepted Meserve’s identification and have since included fun footnotes in their books about Lincoln and Booth appearing in the same photograph.

While this smudged picture of Lincoln contains a good Booth, it is not the best picture of Booth in the crowd. That image is found in the rare book John Wilkes Booth Himself by Richard and Kellie Gutman. Similar to Meserve’s search for all the photographs of Lincoln, the Gutmans tracked down all the pictures of the assassin that were known at the time. The book itself is quite remarkable and only 1,000 copies were printed in 1979. It is rare to see a copy up for sale today for less than $450 with a few copies being offered for even more than that. In this volume, the Gutmans found a image that was very similar to the well known version of the inauguration:

The difference between the common inauguration photo and this one is that the focal point is not on the President at the podium but, oddly enough, on the crowd above him where Booth is standing. This image provides the best detail of the man who would be Booth. It is this image, merged with the common inauguration photo, that I used to create the blog’s current header image.

What has occurred over the years is that, while many people knew Booth was in the photographs of the inauguration, they never took the time to look up which one he was or where he could be found. Instead, they used the best photograph of Lincoln and then just guessed as to which man in the crowd was Booth. The Ford’s Theatre museum is guilty of perpetrating this. They have a large wall display of Lincoln’s second inauguration. As an inset, they have the following:

The man they have highlighted as Booth, is not the same man we have seen in the other photos as being Booth. This man has longer hair and is wearing no hat of any kind. Attending such an important event without a proper hat, no matter how much he disliked the President, was a social faux pas that the ornate and vain John Wilkes Booth would never commit. This man highlighted on the display at Ford’s and on many websites as Booth is not correct.

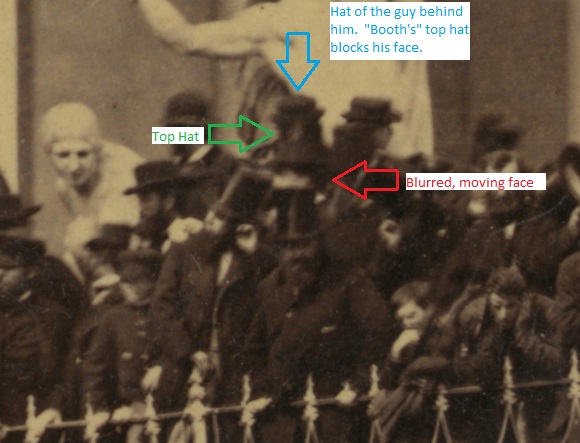

The question arises then, if the highlighted man is not Booth, then where is he? In the well known inauguration photo, with Lincoln addressing the crowd, Booth is still standing in the same place where he was in the other photos. This time, however, he is blocked by the people in front of him:

Booth is partially obscured by the gentlemen in front of him straining to hear. Only his hat and the top of his head are visible, but he is still there.

I hope that this post outlines the misconceptions about John Wilkes Booth at Lincoln’s second inauguration. We know he was there and witnessed the event. There is no guarantee that he is present in any of the inaugural photos, though. The identification made by Frederick Hill Meserve is a theory, like anything else. In my eyes, it is a decent one. The man Meserve says is Booth, looks like Booth to me. I wouldn’t bet my life on it, but it’s a harmless enough theory to support.

Update 2/19/2013: Many people have recently come to this page due to the airing of the wonderful docudrama “Killing Lincoln”. The producers of “Killing Lincoln” created their own composite image of John Wilkes Booth at Lincoln’s second inauguration in the same fashion that I did. They took the best picture of Booth and placed it into the best picture of Lincoln. Here is their result:

Humorously, Booth is standing right next to himself in this version of the picture:

References:

Frederick Hill Meserve’s original identification of Booth in Life magazine

John Wilkes Booth Himself by Richard and Kellie Gutman

The Photographs of Abraham Lincoln by Frederick Hill Meserve and Carl Sandburg

PictureHistory.com – they hold the licensing rights to Frederick Hill Meserve’s collection

Recent Comments