On this date, June 9th, in 1893, a part of the three upper floors of Ford’s Theatre collapsed killing twenty two clerks and injuring over 100 more government employees.

NPS Photo

After the assassination of Lincoln, the government immediately seized Ford’s Theatre. Military guards had been posted to the theatre and access was granted by War Department passes. Matthew Brady was allowed to photograph the interior and members of the stage crew and orchestra were allowed to retrieve their items from within its walls. After the execution of the conspirators on July 7th, 1865, John T. Ford was given permission to reopen his theatre. He announced that the play, “The Octoroon” was to be performed on July 10th. As is shown on the playbills and broadsides from “Our American Cousin”, “The Octoroon” was initially scheduled for April 15th. While Ford sold over 200 tickets for the performance, there was also a large uproar over the theatre reopening after what had transpired within her walls. Ford received this anonymous letter implying retribution if he fulfilled his plan:

“Sir:

You must not think of opening tomorrow night. I can assure you that it will not be tolerated. You must dispose of the property in some other way. Take even fifty thousand for it and build another and you will be generously supported. But do not attempt to open it again.

One of many determined to prevent it.”

For fear of the place being burned, the Judge Advocate ordered a troop of soldiers to the theatre on the night of July 10th, to prevent anyone from attending the play. Ford placed a sign on the door reading, “Closed by Order of the Secretary of War” and refunded the ticket holders. He would not attempt to revive his theatre again.

The government decided its best option was to just retain the property. They began paying John Ford $1,500 a month to lease his theatre. By July of 1866, the government bought the property outright for Ford for $88,000. Even before purchasing the building, the government had started renovating the theatre. They transformed the interior into a three story office building. In December of 1865, the Army Medical Museum moved into the third floor of the space.

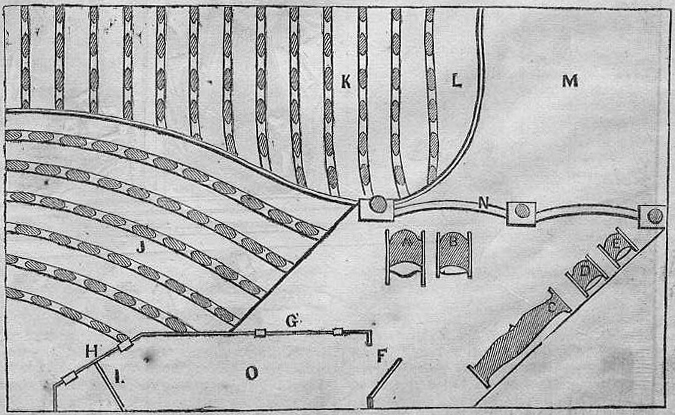

Engraving of the Army Medical Museum housed in Ford’s Theatre from the book, “Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital as a Woman Sees Them” (1874).

The museum would stay in Ford’s until 1887, when a separate building was constructed for their purposes. The Army Medical Museum’s occupancy at Ford’s provided a slightly macabre reunion between Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth. The museum housed pieces of Lincoln’s skull and hair, and Booth’s vertebrae, each taken from their perspective autopsies. Parts of the two men spent over twenty years together at the scene of their last meeting. EDIT: Further research has shown that Lincoln’s skull fragments were not given to the Army Medical Museum until after it had moved out of Ford’s Theatre. Darn.

Lincoln Skull Fragments and Nelaton Probe

Engraving of Booth Vertebrae

The other two floors of Ford’s housed the Office of Records and Pensions run by the War Department. When the medical museum moved out, they took over the entire building. The many clerks employed in the building compiled the official pension records for Civil War veterans and others.

In 1887, the Pension bureau received a new chief, Colonel Fred C. Ainsworth. As a boss, Ainsworth was not a popular fellow. His methods of leadership and his expectations of his clerks was a drastic change from the department’s previous leaders. Old timers who had worked in the office for years found themselves held to greater expectations and increased workloads. While this made Ainsworth an efficient chief, it also made him a very disliked leader. However, Ainsworth was not heartless and tried his best to appease his clerks. Ainsworth was aware of his clerks’ apprehension about the building they occupied. When he first started, he heard rumors that the east wall of Ford’s was unsafe. He made inquiries with his superiors and was assured that the wall was perfectly secure and the whole building was safe. In 1888 and 1889, Ainsworth directed the installation of a new steam heating apparatus and a new plumbing system for the building. Then in 1893, he received permission to install an electric light plant for the building. In order to place the light plant and provide amble ventilation for it, it was required to excavate about twelve feet between two partition walls in the basement. Ainsworth wrote up specifications, gave them to the War Department, and the War Department created a contract and accepted bids. Eventually, the bid by a contractor named George W. Dant was chosen to do the work. During this entire process, no element of danger was discussed by anyone. With proper underpinning of the floor above, the excavation was a relatively safe job.

While this construction was going on, the clerks’ unease about the building increased. Plaster was known to fall from the ceiling and, at one point, part of the first floor was roped off causing the clerks to worry about the structure. None of them however, seem to have brought their concerns up with Colonel Ainsworth. As chief, he continually went into the basement to check on Dant and his men. Dant continually assured him that everything was fine and that the roped off area was just because that particular part of the first floor was to be removed as part of the excavation.

Then, on this day in 1893, tragedy struck Ford’s again. During the course of the work day, with hundreds of clerks and files hustling about, a support pier in the basement excavation area collapsed. The floors above were supported by iron beams, which rested on columns, which rested on the brick piers in the basement. When the one pier gave way, a 40 foot section from all three floors collapsed down. Twenty one clerks were instantly crushed and killed. One would die a few days later from his injuries. A total of 105 clerks suffered injuries, with two more clerks dying as a result of their injuries over the next three years.

Almost as soon as the dust settled, and the dead were dug out, the public demanded to know who was responsible for the collapse. A Coroner’s inquest was held to determine if there was any criminal responsibility. The surviving clerks, furious over the loss of their brethren, used this opportunity to lay the blame on their despised chief, Colonel Ainsworth. On the witness stand they spoke of the building being a death trap long before the accident. They claimed they were told by Ainsworth’s assistants to tip toe on the stairs because they were dangerous. They said they were too afraid to say anything about the conditions for fear they would be fired. The room in which the inquest was held turned into a scene of fury, with all rage directed towards the Colonel. A man who lost his brother in the accident came up behind the sitting Colonel and yelled “You murdered my brother!” Shouts of agreement came from others in the crowd and several rose to their feet moving to close in on the Colonel. Luckily the police lieutenant in the court was able to disperse the impromptu mob. As more and more witnesses took the stand, the outbursts from the crowd increased. All the while, the Colonel sat calmly in his chair, unwavering.

With emotions high, even members of the jury broke decorum. B. H. Warner, a juror, interrupted a testimony and asked for Ainsworth to leave as he was intimidating witnesses with his mere presence. The crowd applauded this suggestion for a full minute glaring at Ainsworth all the while. Ainsworth refused to leave citing it as his right to hear testimony regarding the events. The Coroner agreed. He had no precedent to evict Ainsworth, as he had done no wrong and merely sat there. When the Colonel’s representative, a Mr. Perry, rose to address the room, the crowd yelled at him and hissed. When the room finally gained its composure, Mr. Perry begged the crowd, “I appeal to you as American citizens for fair play.” To this a member of the crowd replied with, “You didn’t give us fair play!” At that point, the tempest roared. The shouts of, “Murderer!” changed to, “Hang him! Hang him!” and the mob approached Ainsworth who continued to sit cool and collected in his chair. The police lieutenant was powerless to disperse the mob. For a brief moment of time, it appeared the Colonel’s life was to end right there by the hands of his angered employees.

The only thing that brought the mob back to its senses was the when the juror who previously spoke, B. H. Warner, stood upon his chair and begged for order. He calmed the crowd back down with the following:

“This outbreak of feeling must be suppressed not by the strong hand of the law, but by the hand of fraternity. I appeal to you to have fair play as American citizens, and not to stain the fair name of the glorious Capitol of this Republic. I appeal to you in the name of the Master who reigns above.”

The inquest continued for the next few days but with increased police attendance that squashed all disturbances before they could start. The jurors of the inquest found Colonel Ainsworth, contractor Dant, the superintendent of the building, and the mechanical engineer of Ford’s guilty of criminal negligence. However, the Coroner’s inquest had no real power. It merely established whether or not the men could be charged with the crime. Despite the findings, the district attorney never charged the superintendent or the mechanical engineer with any crime. Due to the public outcry, however, he did go after Ainsworth and Dant. The defense effectively postponed matters until time allowed the public to cool down.

In the end, the charges against Colonel Ainsworth were dropped as the Coroner’s inquest never proved that he had any knowledge that the building was unsafe. The jurors’ verdict was a product of the emotions of the times and not the evidence. The accident was a travesty, but the Colonel was guilty of no wrong doing. He continued as Chief of the Records and Pensions bureau and worked his way up to becoming the Adjutant General. He died in 1934 and is buried in Arlington.

Of all those involved, it is probably George W. Dant who is to blame for the collapse. It appears that he and his crew did not properly shore up the brick piers around the excavation. With the ground around them gone, the weight of the floors above was too much for the exposed piers. The cause of the collapse was due to the improper support of these piers. While Dant was the most liable for what occurred, by April of 1895 the prosecution gave up its case against him.

NPS Photo

For the clerks who perished, the government paid $5,000 to each of their families. Those who were wounded in the collapse received anywhere from $50 to $5,000 depending on the extent of their injuries.

The inside of Ford’s was rebuilt immediately after the collapse. From 1893 to 1931 the building housed the Government Printing Office under the direction of the Adjutant General. In 1931 the building was turned over to the Department of the Interior and the Osborne Oldroyd’s Lincoln Museum opened on the first floor in 1932. It became a National Historic Site the same year. After being renovated and restored to its 1865 appearance, it reopened as a working theatre and museum in 1968.

While it is well known, the one item of coincidence regarding the June 9th, 1893 collapse of Ford’s is still worth repeating here. At around the same time the clerks of Ford’s were falling to their deaths, another man was being buried in Massachusetts. Edwin Booth, the great tragedian and brother of the assassin, died on June 7th. On the day of the collapse, he was being interred at his final resting place in Mount Auburn cemetery. Despite Edwin’s lifetime of success as the greatest actor of his generation, both his life and death are eclipsed by tragedies at Ford’s Theatre.

References:

Ford’s Theatre and the Lincoln Assassination by Victoria Grieve

Restoration of Ford’s Theatre by George Olszewski

There are many newspaper articles about the inquest and legal proceedings regarding the collapse. I used GenealogyBank searches for Ainsworth and Dant to find several articles. Others can be found in the New York Times’ archive. The most entertaining account (which contains the material about the mob at the first session of the inquest) can be read here.

Other articles about Ainsworth’s legal process: 1, 2, 3

Recent Comments