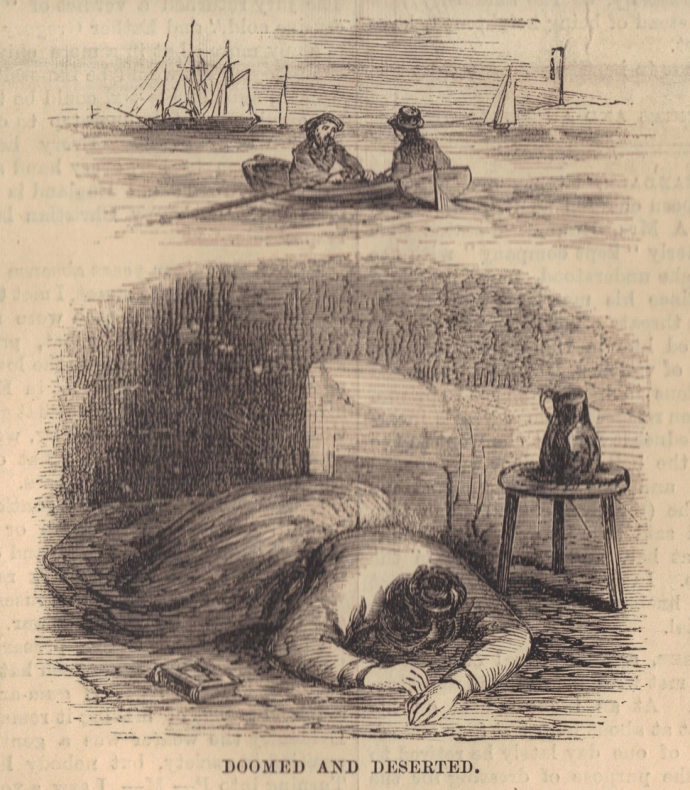

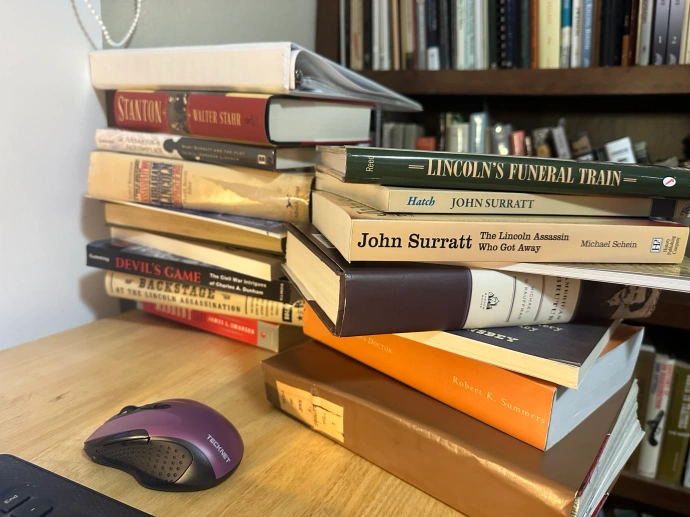

I am conducting an ongoing review of the seven-part AppleTV+ miniseries Manhunt, named after the Lincoln assassination book by James L. Swanson. This is my historical review for the fourth episode of the series “The Secret Line.” I previously posted a prologue to this episode, which contained a summary of the episode and my overall thoughts regarding the historical accuracy of this series. For full context, I recommend you read that post first before continuing. To read my reviews of earlier episodes, click the hyperlinked episode numbers that follow: Episode 1, Episode 2, Episode 3, Episode 4a.

Episode 4: The Secret Line

A summary of the events of this episode can be read in my Prologue post.

Before diving into the fact vs. fiction of this episode, I want to highlight things that I liked about this fourth episode of Manhunt.

- Mary Simms quits

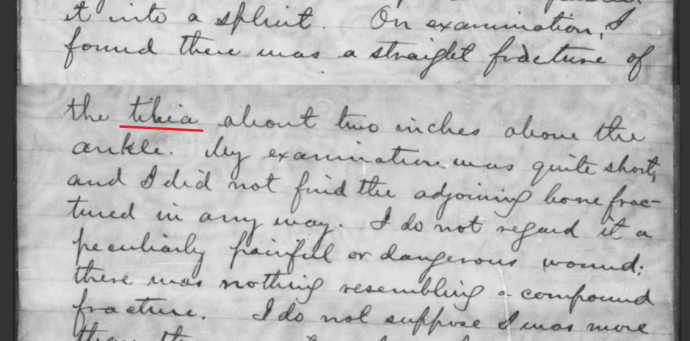

Chronologically, the real Mary Simms left Dr. Mudd’s farm about 5 months before the assassination. At the beginning of this episode, we finally get to see what this separation might have been like. I was happy to see Mary’s emancipation from Mudd’s finally come to fruition in the series. It was rewarding for us, as the audience, to see her essentially tell Dr. Mudd off before leaving to strike it out on her own. The series finally made it clear, after being pretty ambiguous up to this point, that Mary Simms was not being enslaved by Dr. Mudd at this time but was a hired servant. Slavery ended in Maryland in November of 1864, and it was during the same month that the Mary Simms left the Mudd farm. According to her testimony, Dr. Mudd had beaten her after emancipation came, and so she left rather than continue to endure such abuse. She left the Mudd family and never looked back. During the trial, one of the defense witnesses was Julia Ann Bloise. She had been a hired servant at Dr. Mudd’s during the year 1864. She testified that Dr. Mudd never beat Mary Simms during the time she was employed there. However, she did state that Mrs. Mudd (who is absent in the series along with Dr. Mudd’s children) “struck her about three licks with a little switch” for going out walking on Sunday evening without permission. So, it may be that this physical abuse was the last straw for Mary, who was no longer bound to tolerate such things. Watching Mary Simms finally finding her voice and breaking through the mental slavery she had endured is well shown in this episode.

- “We’re Not Our Brothers”

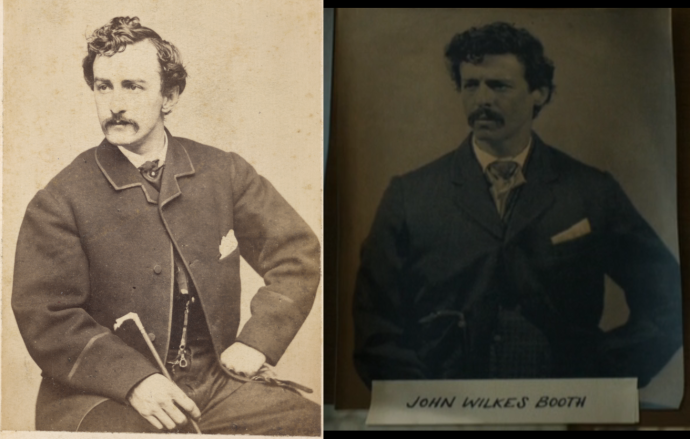

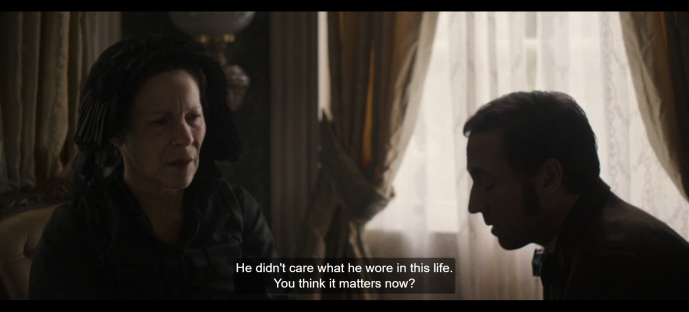

In the New York City scene, we see Mary Lincoln conversing with Edwin Booth at a private wake for President Lincoln. This scene is entirely fictional, but I still really liked the conversation between this Booth and Mrs. Lincoln. Edwin recounts a line the President asked him to recite once, and Mrs. Lincoln recalled how much Abraham appreciated Booth’s performance of Hamlet and the theater in general. Edwin compliments the late President’s own oratory skills and then apologizes to Mrs. Lincoln personally for his brother’s crime. To this, the incredibly understanding Mrs. Lincoln states, “My brothers are Confederates, too. We’re not our brothers.” It is a very touching moment between two historical figures who suffered greatly due to the actions of John Wilkes Booth.

Of course, as I have noted before, Mrs. Lincoln did not take part in the funerary activities surrounding her husband. She did not travel with the funeral train and, as far as I know, did not attend any private wakes in New York City. Edwin Booth, likewise, would never have made an appearance at such a function, even if it did occur. After hearing of his brother’s crime, Edwin secluded himself and retired from the stage for nine months. Under no circumstances would propriety have allowed Edwin to attempt to converse with the widow Lincoln about her loss at the hands of his own blood. While the President and First Lady had seen Edwin Booth perform in February and March of 1864 when the tragedian played at Grover’s National Theatre in Washington, Lincoln and the actor never met in person.

Still, I like the “What-if?” scenario played out in this scene. It was interesting to see these two historical figures bond somewhat over the tragedy that connected them.

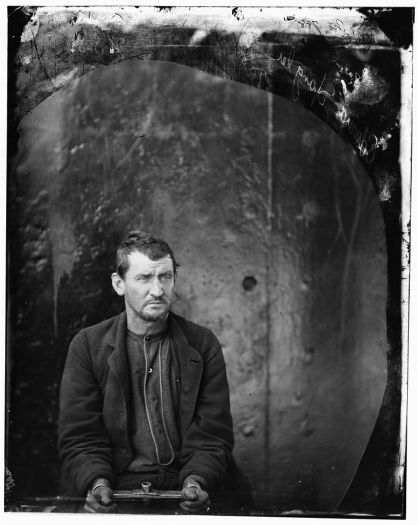

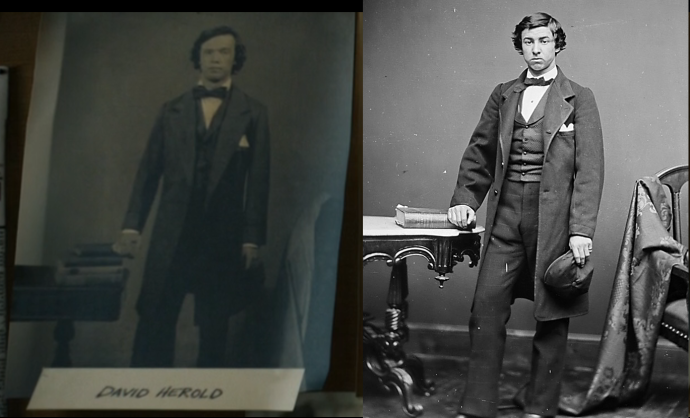

- Command Performances

Most of this episode’s action revolves around Edwin Stanton’s investigation into George Sanders’s fictional machinations, so the subject of the manhunt is quite secondary. This makes sense since this period is supposed to cover the four and a half days Booth and Herold were hiding out in the pine thicket. As someone who has personally reenacted this part of Booth’s escape, I can tell you that there is only so much content to be drawn out in the woods. Still, I believe credit is due for the main scene between Booth and Herold in the thicket. During this scene, Davy reads Booth’s diary (which, again, was never a book-length biography as implied but a few hastily scribbled pages done during the escape) and asks him about his childhood. Booth mentions having dressed up some of his father’s slaves as royalty, and he and his sister (likely Asia) would give them command dramatic performances. This is reminiscent of some of the stories in Asia’s biography of her misguided brother. She recounts instances where they practiced Shakespearian plays together, including reciting Romeo and Juliet from a balcony at Tudor Hall.

The balcony outside of John Wilkes Booth’s room at Tudor Hall, known as the Romeo and Juliet balcony.

Junius Brutus Booth, the elder, did not approve of slavery yet still participated in it. The bulk of the Black servants and fieldhands at the Booth farm were rented from other neighborhood enslavers. Joe and Ann Hall, two servants for the Booth family, had several children of the same age as the Booths, so JWB and Asia often found regular playmates among the Hall children.

Young John Wilkes Booth grew up in a racial hierarchy in which he was at the top. As he got older, the future assassin took on a paternalistic view toward those who were enslaved. This white supremacist view held that Black men and women were incapable of taking care of themselves and needed the white man’s guiding hand. In this way, Booth convinced himself that slavery was beneficial for Black Americans, whom he saw as children regardless of their age. This view was very common and perpetuated the “good master” myth amongst enslavers. Booth’s joking in this scene about dressing up enslaved children in fancy clothes demonstrates his view that they were little more than playthings for his amusement. It effectively demonstrates his learned version of racism.

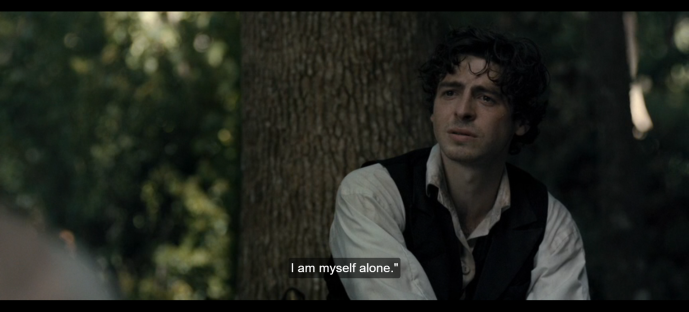

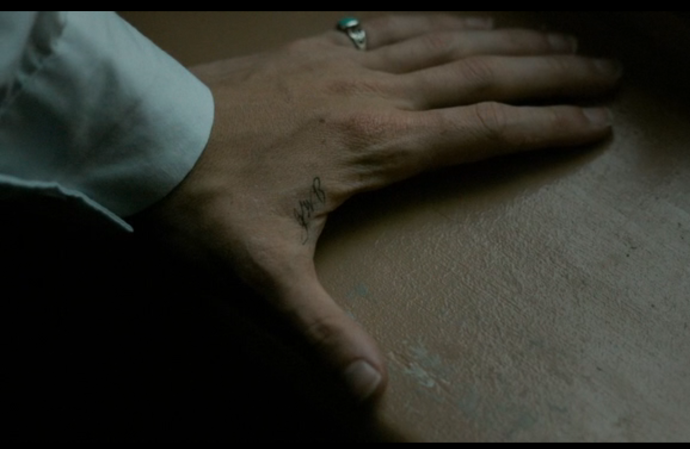

- “I am myself alone.”

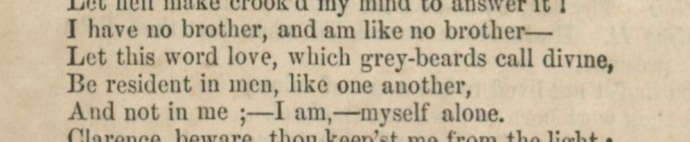

In the same scene, Booth deigned to recite something for Herold’s amusement. Davy requests poetry and asks Booth to recite some verse from Edgar Allan Poe. It’s actually rather fitting that the series has Herold announce that he likes poetry because one of the last known writing samples we have for the fugitives is a page of poetry that they wrote while on the run. However, rather than poetry, Booth convinces Davy to let him recite a few lines from Richard III instead, noting that he was well acclaimed in the role. This is truthful, as Richard III was perhaps Booth’s best role. Booth then proceeds to recite lines that aren’t in the original version of Richard III but do appear in the Colley Cibber version, which was the version of Richard III that was known and enjoyed by theater patrons. The lines go:

These lines come from John Wilkes Booth’s personal promptbook for Richard III. This book is in the collection of the Harry Ransom Center and has been completely digitized. Click the image to flip through Booth’s promptbook and see the assassin’s own handwritten notes.

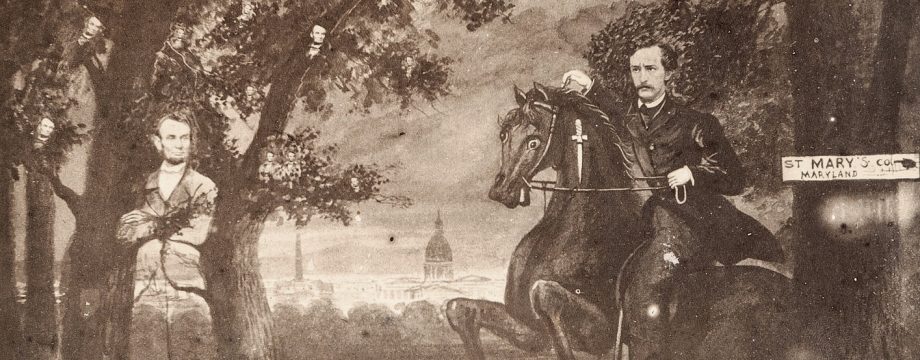

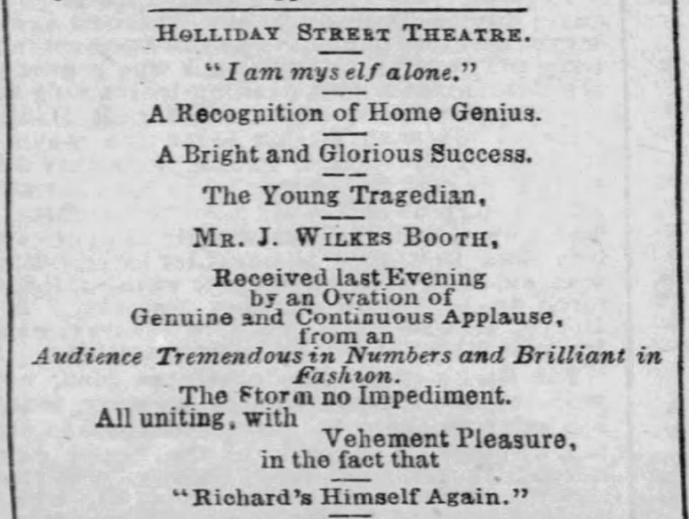

This was a great quote for the production to pull. Not only does it pair well with the preceding flashback of Booth with his brother (I break that down below), but it is also a line that Booth was well acquainted with. When Booth made his debut as a starring actor in his hometown of Baltimore, theater manager John T. Ford did all that he could to draw crowds to his Holliday Street Theatre. Part of that advertisement was to play up the Booth brother angle and get the populace excited to see this new son of the legendary Junius Brutus Booth. Thus, Ford advertised Booth’s Richard III performances with the lines “I am myself alone,” daring the audience to come out and judge whether this younger son of Booth would surpass his brothers and late father.

In better times, this line from Richard III was one that helped gain audiences and bring Booth success. Yet, in this scene, the line is nicely paired with the true loneliness Booth is feeling due to his own actions.

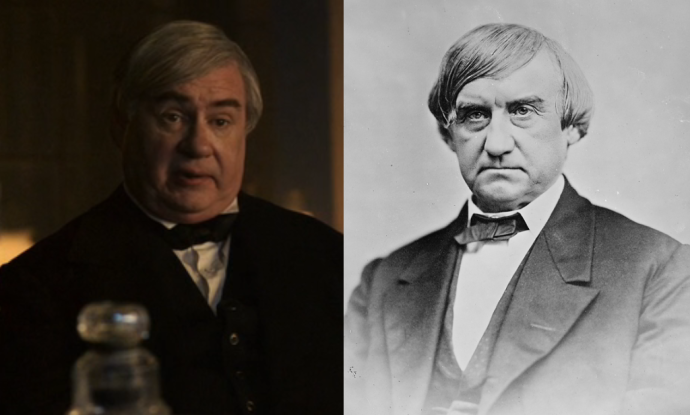

I noted in my prologue post for this review that I wouldn’t really be dealing much with the Stanton storyline in this episode since it is 99% fiction. The scene of Edwin Stanton and George Sanders pulling pistols on each other made for some engaging drama, but the circumstances leading to this moment (and the moment itself) are complete fantasy. There are general things that were true, such as the Dahlgren affair, the attempt to burn New York City, and the Yellow Fever plot against Northern cities, all of which were real events that happened. However, none of these happened as described or portrayed in this episode. Honestly, the easy guide for this episode is that if you see Stanton doing it, it’s most likely fictional.

Still, I wanted to address a few things in this episode related to the Lincoln assassination and Booth family history.

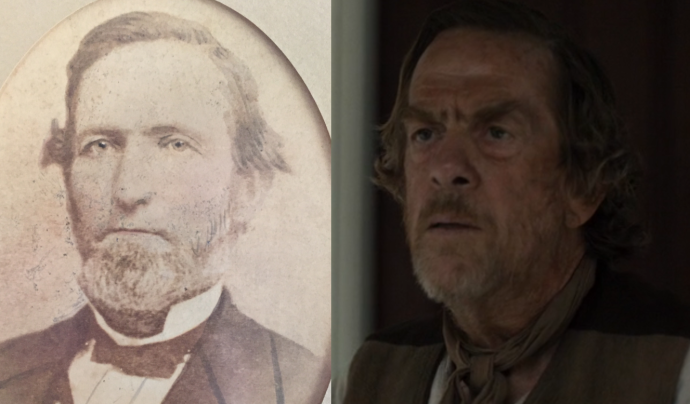

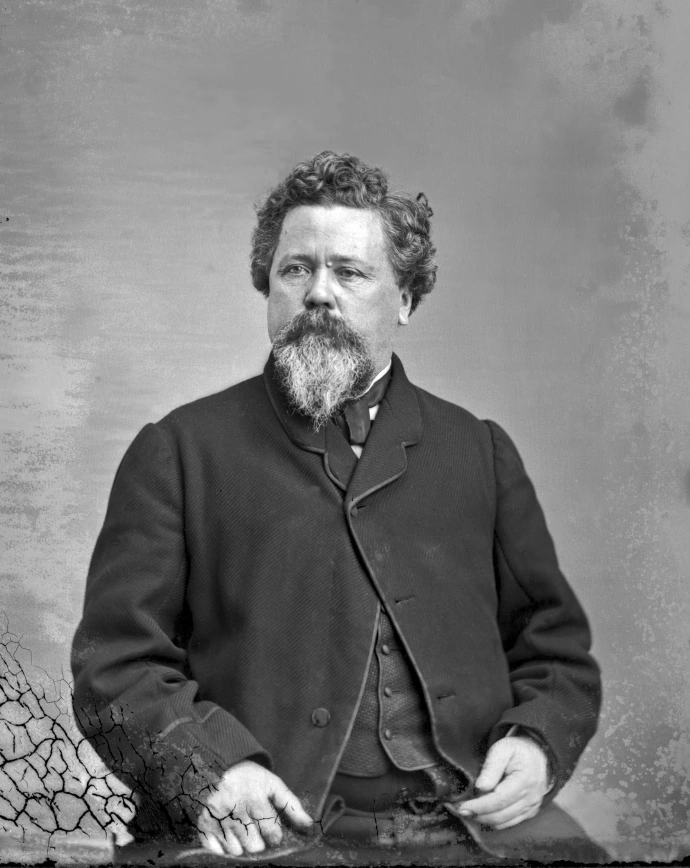

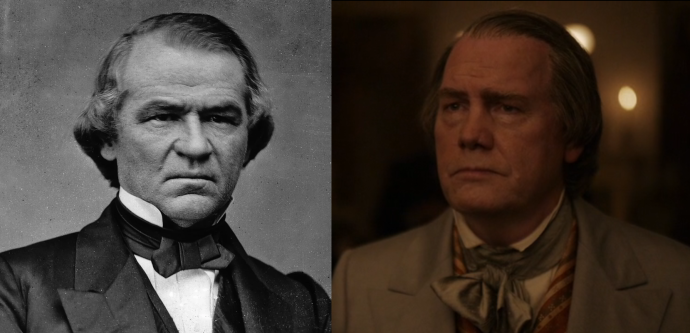

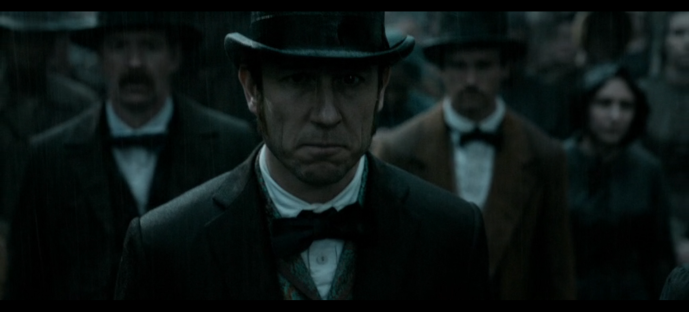

1. Edwin Booth’s character

As I stated above, I enjoyed the fictional scene between Edwin Booth and Mary Lincoln in this episode. Actress Lili Taylor does a great job portraying a far less manic Mary Lincoln, and actor Nick Westrate bears a good resemblance to the noted tragedian.

However, aside from their scene together, this series does not portray Edwin Booth very accurately. After chatting kindly with the widow Mary, Edwin Booth interrupts Stanton’s conversation with Robert Lincoln and aggressively asks the War Secretary, “How do I restore my name? A photograph with General Grant? A White House performance, perhaps?” In a few lines, Edwin has gone from a sincere and apologetic figure to a completely self-absorbed fake, more concerned with his name than with the tragedy of the nation. The real Edwin never acted so duplicitiously. He understood the importance of mourning and recused himself from the public eye. He swore off the stage for good, and it was only the clamoring of the public that convinced him that he was not blamed for what Wilkes had done. Still, out of respect for the fallen President and the knowledge that his kin had committed such an act, Edwin Booth never performed in Washington, D.C., after the assassination. He even turned down offers from Presidents and Congressmen to play the capital city in the decades to follow but always refused. In the days after the assassination, Edwin and the rest of the Booth family were filled with a unique form of grief as they mourned both the President and their own brother. The series’ decision to portray Edwin Booth as insensitive and two-faced is a great disservice to the real man who endured an unimaginable public and private grief.

2. Richmond Again

During his conversation with Sec. Stanton, Edwin Booth states that he and Wilkes had stopped speaking on account of “politics” and because “Wilkes always played a victim” to Edwin. The actor agreed with the Secretary’s assessment that Wilkes saw himself as a hero, and Edwin claimed that upon their last meeting, Wilkes had told him that he “had love only for the South.” According to Edwin, the last time they saw each other was the day Richmond was defeated, and his brother “mourned Richmond more than I’ve seen him mourn a person.”

This ending statement is notable because it completely goes against everything we’ve seen up to now. I’ve pointed out in my prior reviews how illogical this show has been in showing John Wilkes Booth incredibly eager to get to Richmond as the real assassin was well aware that there was nothing for him in the fallen Confederate capital. Yet the miniseries has continually pushed Richmond as Booth’s intended destination. In the prior episode, Samuel Cox tells the fugitive there’s nothing there anymore, yet Wilkes refuses to accept this truth. Through Edwin Booth’s words, the series has accidentally stumbled onto a truthful statement: that John Wilkes Booth was well aware of Richmond’s fall and never would have wanted to go to the Union-occupied city. And yet, two minutes after Edwin says these words, we have the scene of Herold and Wilkes in the pine thicket still talking about going to Richmond. It’s baffling.

In reality, the brothers had not stopped speaking. Edwin knew his brother was a secessionist and supported the Confederacy during the war, and Wilkes knew his brother had voted for Lincoln. These facts did cause friction in the family, but really not to a greater degree than could be found present in countless families with split sympathies. Still, the brothers had a fairly fierce argument about the war in August of 1864, which resulted in Wilkes storming out of Edwin’s home, but it did not cause a permanent fissure. For the sake of their mother, the Booth brothers decided that it was better not to discuss politics together, though conflicts over the war continued to pop up between them. Still, Wilkes visited his brother in New York and was likely present when Edwin completed a career highlight of 100 nights straight of Hamlet in March of 1865. They were different people who lived in different worlds, but they supported each other professionally.

3. The Show Must (and Did) Go On

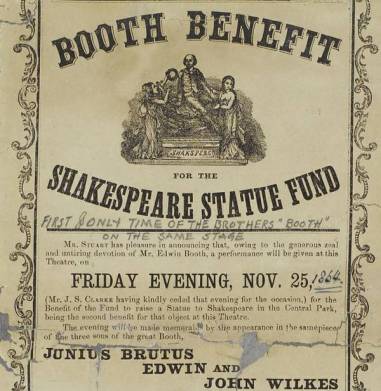

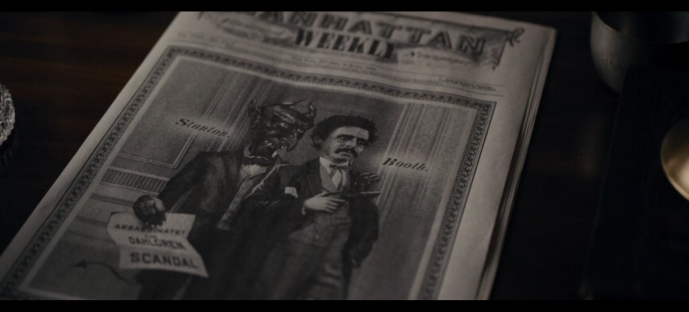

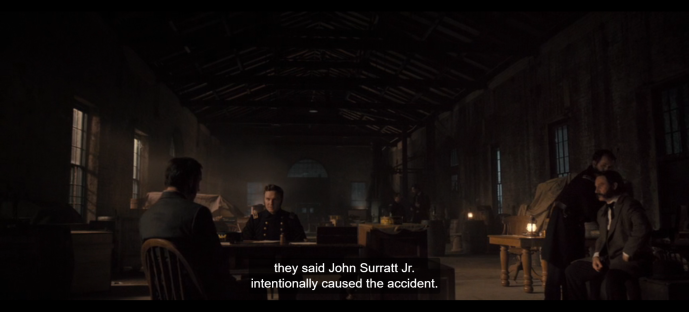

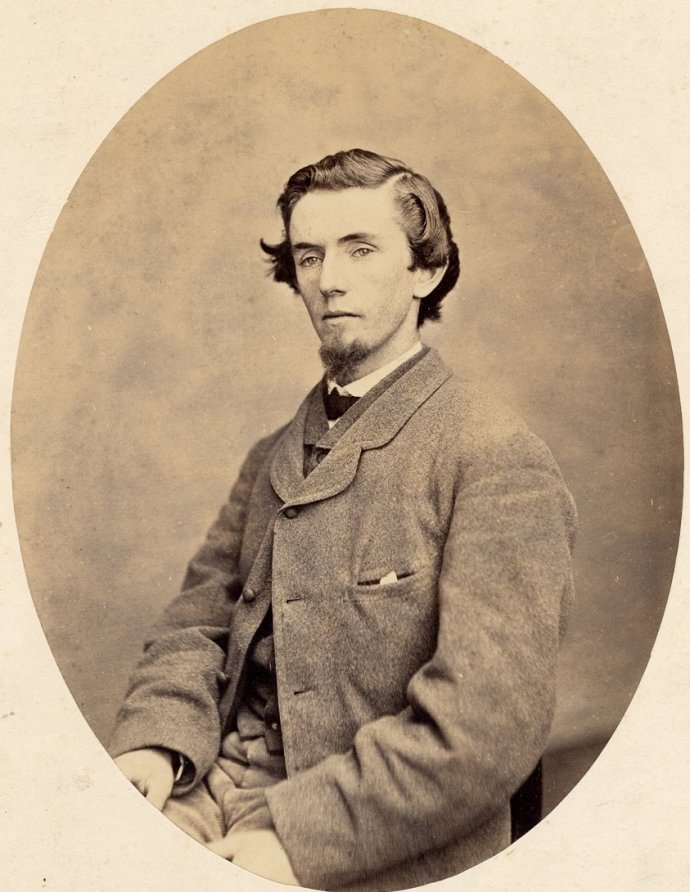

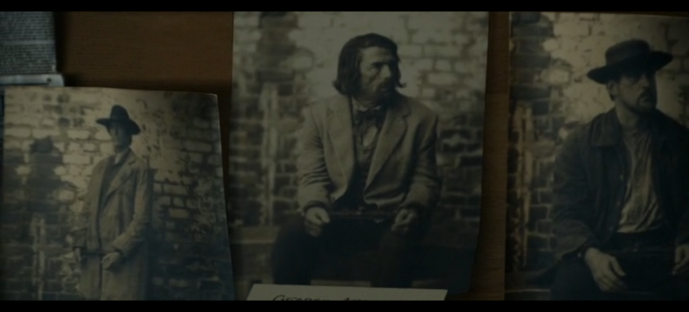

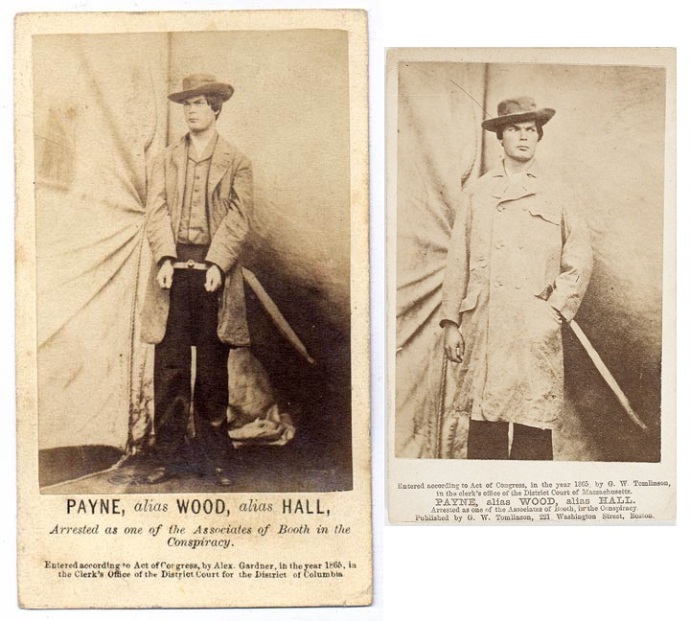

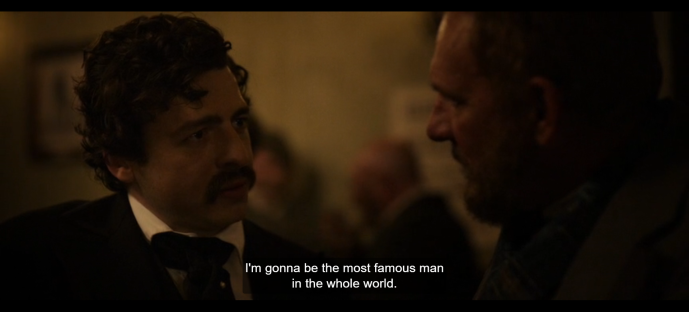

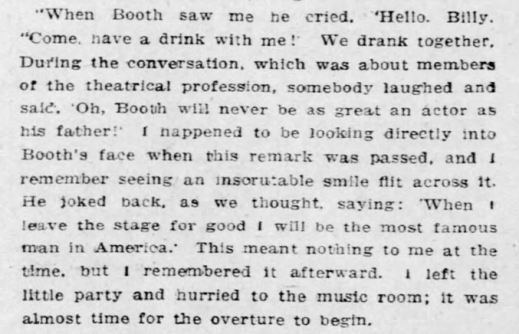

Immediately following Edwin’s scene with Stanton, we are given a flashback to the night of the New York City arson plot, which occurred on November 25, 1864. This was the same night that the three acting Booth brothers, John Wilkes, Edwin, and Junius, Jr., shared the stage together for the first time. They performed the play Julius Caesar as a benefit performance to raise funds for a statue of William Shakespeare in Central Park.

This Booth benefit was the project of Edwin Booth, who had been trying to arrange it since early in the summer of 1864. However, John Wilkes’s travels to the Pennsylvania oil region (and secret early plotting to abduct President Lincoln) had delayed the performance by a few months. The series is correct that an attempt was made to burn down several hotels in New York City on this date, including the LaFarge Hotel adjacent to the Winter Garden Theatre, where the Booths were performing. However, the details of the fire plot are misrepresented, and George Sanders has nothing to do with it.

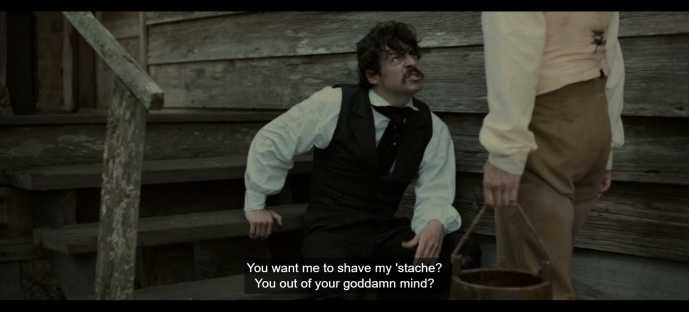

In the flashback, an erroneously mustachioed Wilkes and Edwin are seen outside of the theater, watching the burning hotel. The elder brother, June, must be off taking a smoke break, as he is nowhere to be seen. Wilkes comments that while “they had to evacuate tonight,” he’s “not leaving the play.” This implies that this one-time show was canceled on account of the fire, but this is not the case. During the second act, firemen rushed into the theater and interrupted the show with the news that the nearby hotel was on fire. In the chaos that followed, Edwin broke character and assured the audience they were not in danger. A bit later, a squad of police entered and also reassured the audience that the fire had not spread to the theater so the play could go on. The Booths completed their benefit, raising about $4,000 for the Shakespeare statue that was unveiled in Central Park in 1872.

4. JWB and Edwin’s Relationship

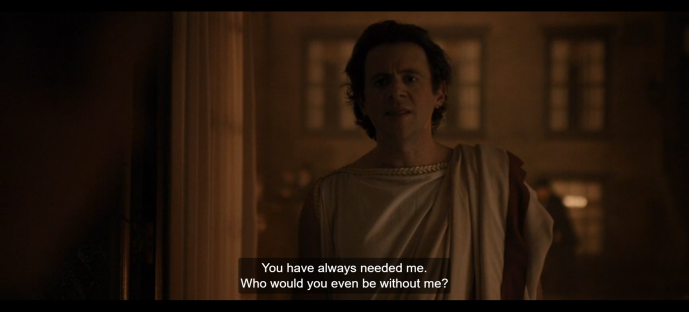

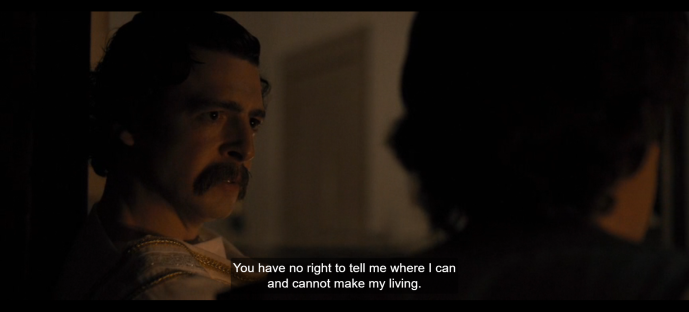

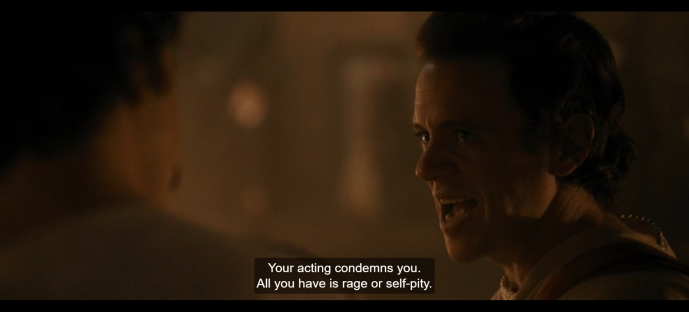

I truly do not understand why Edwin Booth was made to play the villain in the flashback scene outside of the Winter Garden Theatre. His interactions with his brother appear to justify why Wilkes “played the victim” to him. Edwin is incredibly dismissive and talks down to Wilkes. Perhaps we are supposed to side with Edwin due to his claims that Wilkes’s Confederate sympathies are staining the Booth reputation. However, the tone of this scene makes Wilkes come across as the sympathetic Booth, belittled and abused by his demeaning older brother. After watching this scene, one would come away with the idea that Edwin is partially to blame for what his brother did, he having mistreated Wilkes to such a degree as to drive him to such extremes to be recognized.

Needless to say, there is a lot wrong with this portrayal of the Booth brothers. While Edwin was well aware of his brother’s Confederate sympathies, this was not something that either brother broadcast widely. Part of the shock of the Lincoln assassination was that the perpetrator was John Wilkes Booth, a man very few knew harbored such strong anti-Union beliefs. While some actors and stagehands knew Wilkes was sympathetic to the South, he shared this in common with a great many others in the business, and he was not considered extreme on the subject until his attack on Lincoln.

One of the most commonly repeated myths that I come across regarding the Booth brothers and their theatrical careers is the idea that Edwin split up the country and told which brother where he could perform and where he couldn’t. This is usually followed by the claim that Edwin took the North, gave California to June (who resided there), and then left the South for Wilkes. In this flashback scene, such an arrangement is alluded to with Wilkes pushing back against Edwin telling him where he can and cannot act.

After another insult from Edwin, Wilkes defiantly says that he doesn’t need the northern cities of Boston, New York, or Philadelphia and that he will happily play Virginia and other Southern states that support the “cause.” And this is where the illogical nature of the “Edwin splitting up the country tale” shows up. During the Civil War, civilians like the Booth brothers had no access to the Southern states. While Wilkes would have undoubtedly liked to have been on the Southern stages, he was cut off. There was a war going on, and you couldn’t just travel to the South for fun. If Wilkes had risked it all and illegally crossed into the Confederacy, he would never have been welcomed on the Northern stages ever again. That act would have truly stained his reputation. Had Wilkes not committed his deed, I have no doubt he would have started performing in the South after the war was over when it was allowed. But the idea that Edwin ordered Wilkes to play exclusively in the South is ridiculous. Aside from an acting engagement to the Union-occupied city of New Orleans, John Wilkes Booth did not visit the Confederate states after the Civil War began. He made his home in the Union and stuck with it, much to his (and ultimately the nation’s) regret.

This scene also shows Edwin being very dismissive of his brother’s acting ability. As I wrote in my review for episode 1, this series has done a lot to negate the level of fame John Wilkes Booth had gained. In reality, after seeing Wilkes perform in 1863, Edwin Booth wrote to a friend, “I am happy to state that [Wilkes] is full of the true grit – he has stuff enough in him to make good suits for a dozen such player-folk as we are cursed with; and when time and study round his rough edges, he’ll bid them all “stand apart…” In the early days of 1858 and 1859, when Wilkes was still a lowly stock actor learning the stage, he performed alongside Edwin when the latter came to visit as the touring star. At the end of these performances, it was not unusual for Edwin to bring his younger brother to the footlights so that he might brag about him to the audience. Edwin wanted his brother to succeed and would never have insulted his acting in the manner shown in the series. By 1865, the two brothers were close to equal in their dramatic abilities, with Edwin being at his best in the brooding roles of Hamlet and Othello, while Wilkes was the better action star in Richard III and romantic Romeo. Despite their political differences, the real Edwin Booth was always very supportive of his brother’s histrionic talents, and Wilkes respected his brother’s skills as well.

At the end of their scene together, a woman walks up and asks for an autograph. Wilkes, assuming the remark is directed towards him, says yes, only to see the woman hand the playbill over to Edwin. In taking the playbill, Edwin gives his brother an extremely condescending look. Once again, I couldn’t help but think of the short-lived comedy show the History Channel attempted called The Crossroads of History and a very similar scene where Wilkes meets some “fans” while drinking in the Star Saloon next door to Ford’s Theatre. It has the same energy.

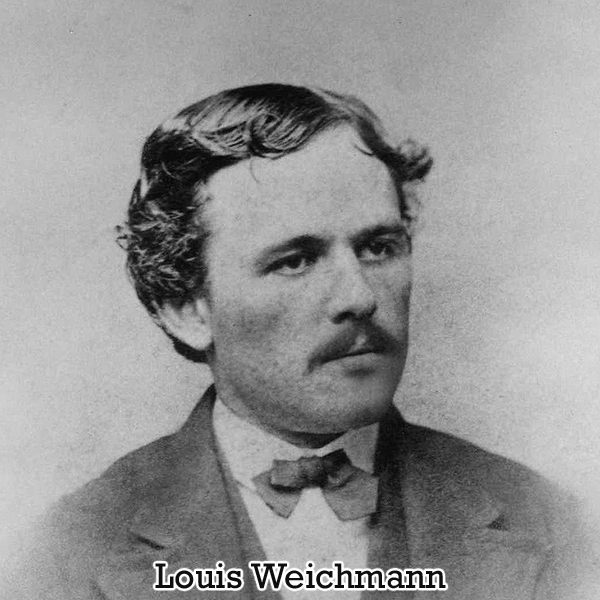

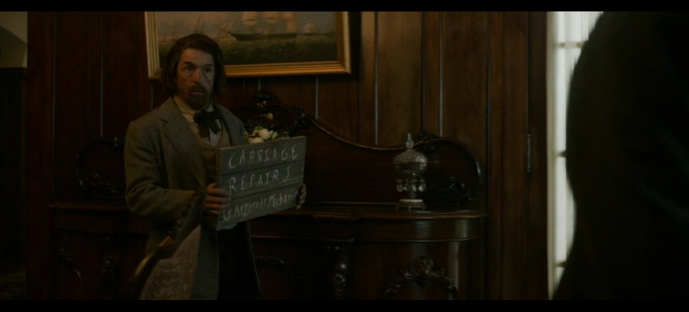

5. Oil Investment

This is the second episode in which Layfayette Baker mentions Booth’s oil investments. In episode 2, he informed Stanton that “Booth had four meetings with Wall Street bigwigs, wanted them to invest in a Pittsburgh oil rig with him.” In both episodes, these comments are followed by theories that “oil investment” was code for the assassination plot. There is a degree of truth in these lines, but they are couched in incorrect information. John Wilkes Booth was convinced by John A. Ellsler, the manager of the Academy of Music theater in Cleveland, to invest in the Pennsylvania oil region in December 1863. The pair recruited another man, Thomas Mears, to join them in the venture. Mears was a noted prize fighter and gambler. The three men dubbed their oil business The Dramatic Oil Company and started looking for land to acquire. In 1864, they purchased 3.5 acres near Franklin, PA, about 80 miles north of Pittsburgh. They purchased all of the equipment needed to dig an oil well and hired men to do the job. They christened their well the “Wilhelmina,” named after Thomas Mears’s wife.

Several years ago, I visited the oil region and shot some shaky videos of the area around Booth’s oil interests. Today, I realized that I had never done anything with that footage, so I just uploaded the series of videos to YouTube. If you’re interested, you can check out this playlist of videos to learn more about JWB’s attempt to become an oil tycoon.

So, it is well proven that John Wilkes Booth had legitimate oil investments. None of his oil meetings involved George Sanders or any “Wall Street bigwigs,” as the miniseries claims.

However, to be fair to the series, Booth did use the cover of having been successful in the oil business in order to explain away his retirement from the stage. When friends and fellow actors inquired of Booth why he was not acting during the 1864-1865 theatrical season, he lied and said that he had made a fortune in oil. In reality, the oil business had been a financial loss to the actor, and his real interest during this period was working on his plot to abduct President Lincoln. So, in a way, the oil business became a cover for Booth’s real plot, but not in the way the series implies.

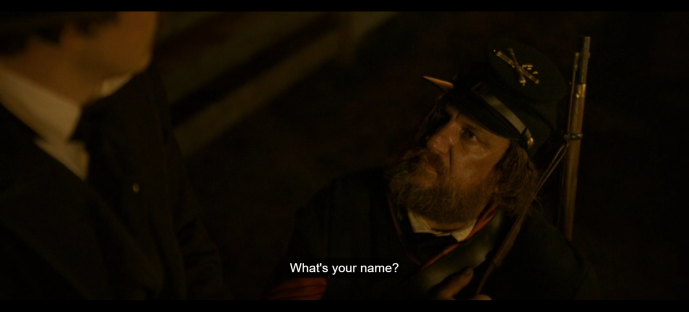

6. Getting Booth to the River

Thomas Jones (aka The River Ghost) shows back up in this episode. Snacking on a stick, he approaches Booth and Herold and tells them the time is right to head for the Potomac River. The trio walks through the windy woods, and at the end of the episode, they are shown at the bank of the river. Booth and Herold enter a small rowboat and are pushed off into the water by Grizzly Adams, who states, “Virginia will welcome you with open arms.” As Herold starts to row, Booth finally acquiesces to Davy’s earlier request for a reading from the works of Edgar Allan Poe. The actor then recites lines from Poe’s famous poem, “The Raven,” and they slip out into the dark river for uncertain shores.

With the suspenseful music in the background and the cuts back to Stanton consulting a map of “the secret line” that he discovered (nonsense, of course), Booth’s recitation is effective and would have been the best ending for the episode in my opinion.

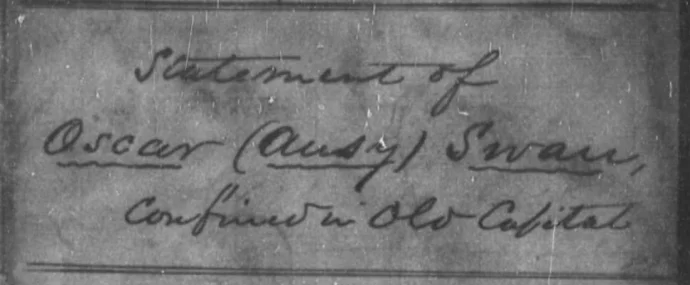

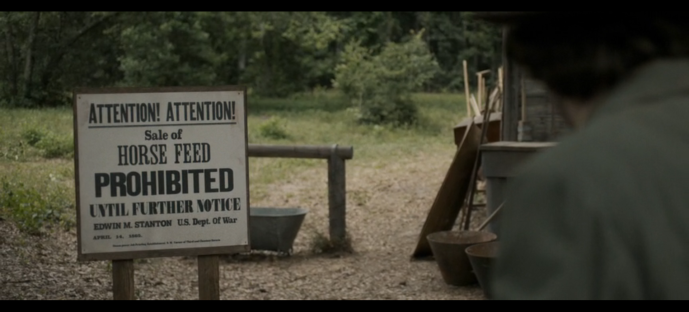

Of course, the series only gets this part of Booth’s escape right in the big picture and not in the details. After learning that a large detachment of troopers were heading from Charles County (where the fugitives were hiding) to St. Mary’s County to the south, Jones knew that the night of April 20th was his best bet to get the men to the river. He, of course, waited until after sundown and gathered the men up. Jones arrived on horseback, and it was decided that the injured Booth would ride atop the horse while Herold walked beside it. The trio proceeded with Jones walking about 50 yards ahead of the pair, checking to make sure the cost was clear and then whistling for them to come forward. Jones would then venture another 50 yards and repeat the process. Thus, it took hours for the men to travel the four miles from the pine thicket to the spot on the Potomac River where Jones had had his servant, Henry Woodland, hide a small boat.

Since I’m apparently highlighting my own videography in this review, here’s a part of my John Wilkes Booth in the Woods reenactment from a decade ago that covers this part of Booth’s escape:

The real Thomas Jones was less certain about the welcome Booth would receive in Virginia but did direct the men to the home of Elizbeth Quesenberry. He gave them a candle and showed Booth the direction on his compass that would get them to Mrs. Q’s home on Machodoc Creek. Booth thanked Jones for the care he had given them and even gave him some money for the loss of the boat. Jones watched as the men headed out onto the river with Herold rowing. Booth attempted to cover the light of the candle with his coat as he steered the boat using an oar and kept a close eye on the compass needle. In truth, a hunched-over Booth trying to hide a candle flame would not have been as powerful as the scene the series provided, so I do prefer the series’ artistic take on this.

Quick Thoughts:

Here are some more things that stood out to me while watching episode 4 that I just don’t have the time to go into deeply.

- The first scene and one of the flashback scenes between Lincoln and Stanton revolve around the Dahlgren Affair. This was a real and still very mysterious incident in which supposed assassination orders against Jefferson Davis were found on the body of a Union colonel, Ulric Dahlgren. Such orders, if genuine, were seen as a violation of the traditional rules of war and, thus, justified similar instances of black flag warfare on the part of the Confederacy. The truth behind the Dahlgren orders and whether they were real or a Confederate forgery will never be known for certain.

- Mary Simms is comfortable quitting Dr. Mudd’s because she has a land grant from the War Department. She said the land was taken from an enslaver and was compensation for all the work enslaved folks had done. I’m not an expert on land grants and don’t know the ins and outs of the Freedmen’s Bureau after the war, but I do not think they took land from enslavers and gave it to former slaves, at least not on a large scale. While some properties were seized during the war, like General Lee’s property in Arlington, I have never heard of swatches of land in Southern Maryland having been seized and then turned over to formerly enslaved individuals. Grants did occur in the West on land taken by the government from Native tribes, but I have a hard time believing that the War Department would seize much land in Maryland, a Union state that never seceded. I’m happy to be proven wrong on this, but I have never read or heard about land in Southern Maryland being given to those who were recently freed from slavery.

- It’s a little thing, but George Sanders keeps talking about how New York City is “his city.” Dude, you’re from Kentucky. Just like KFC and Col. Sanders. Calm down.

- The stabbing attempt on Stanton by a person in a Lincoln mask is never explained. We have no idea who it is or why they were targeting the Secretary of War. It’s a fight scene that serves no purpose.

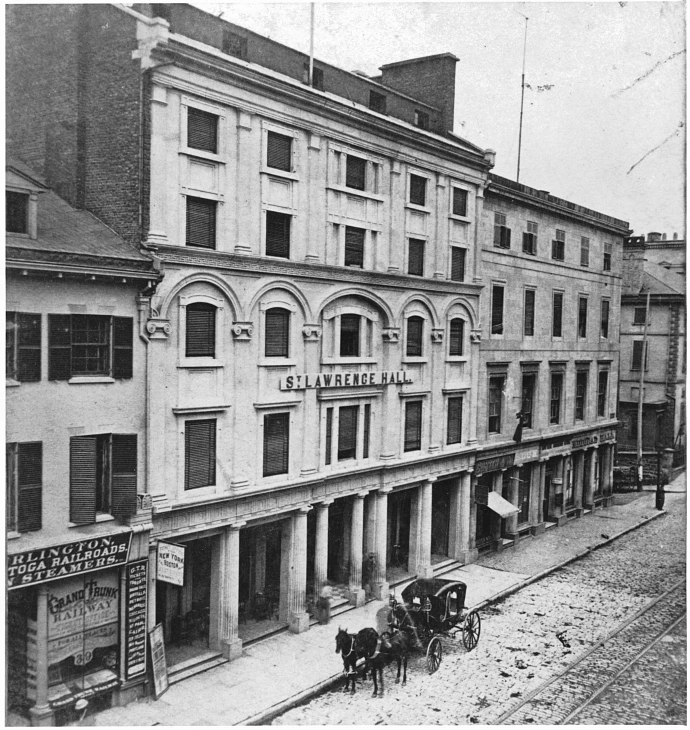

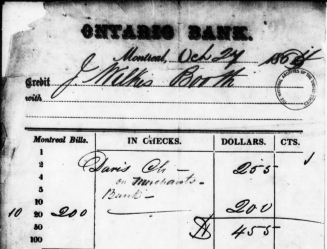

- After merely theorizing that Sanders was the source of the “$500” that Booth deposited in a bank in Montreal back in episode one, Stanton says this definitively to Sanders in this episode. We do not have any evidence that Sanders was the source of the $455 that Booth deposited. It could have easily been Booth’s own money, and since he never withdrew it, we don’t know his purpose for it.

- My family had a pet cockatiel when I was growing up, so I was curious about George Sanders’s having one named Lady in this episode. I wasn’t sure if cockatiels had been exported from Australia or had even been domesticated by the 1860s. Some online sources state that the first cockatiels arrived in Europe in the 1830s, but these lack any sources. When I search newspaper archives for the word cockatiel (and its spelling variants), the first hits I get in the U.S. are from the 1880s. The most humorous result was this advertisement for an exotic bird exhibition in Harrisburg, PA that featured a pair of cockatiels amongst many other feather marvels:

So, I think it unlikely that George Sanders, or anyone in America really, had a pet cockatiel in 1865. But, since we are supposed to believe that Sanders is the Elon Musk of his day, perhaps this exotic bird is to show us just how rich he truly is. Still, you would think he would get a decent-sized cage for his prized parrot. Poor Lady can’t even stretch out her wings without hitting the side of her prison. And, despite Sanders’s claim that he can leave the door open and Lady would never fly out, that bird is clearly itching to escape in the one shot where the door is open.

- There’s a lot of unintentional humor in this episode, such as Stanton scolding Robert Lincoln and telling him to get it together, the random V for Vendetta masked assailant, and Stanton seeming to impersonate Clint Eastwood from Sudden Impact about to tell Sanders to “Make my day” at gunpoint. The episode also ends with a bit of unintentional humor. In the last scene, we see Stanton, his son Eddie, and a single Union soldier all on horseback. The U.S. Capitol building is in the background on the other side of the Anacostia River, and Stanton has his fictional secret line map in hand. The men set off down the road away from Washington with the Union soldier saying, “To Virginia.

But, the thing is, they are not headed to Virginia. They are heading down the road into Southern Maryland. You can’t get into Virginia from that road unless you have your own boat (like Booth). There was no bridge connecting Southern Maryland to Virginia. If Virginia was their destination, then they should have gone back into D.C. and crossed directly into Virginia via the Long Bridge. I understand that not everyone is familiar with the geography of the area, but hearing the soldier say, “To Virginia!” and knowing that they cannot get to Virginia from there without a boat is humorous to me. Luckily, Stanton has already proven he can teleport himself around the country, so it won’t be much of a problem for him.

That’s my historical review for episode 4. While I have already seen the remainder of the series, I am going to refrain from commenting on episodes 5, 6, and 7 until I have time to write my reviews for those episodes individually. I can’t say when I’ll complete my next review, but I promise to get them all in time.

Until then,

Dave Taylor

Recent Comments